Rx 17 / Young Woman Writing

To paint, not the thing, but the effect it produces.

—Stéphane Mallarmé, in a letter to Henri Cazalis (1864)

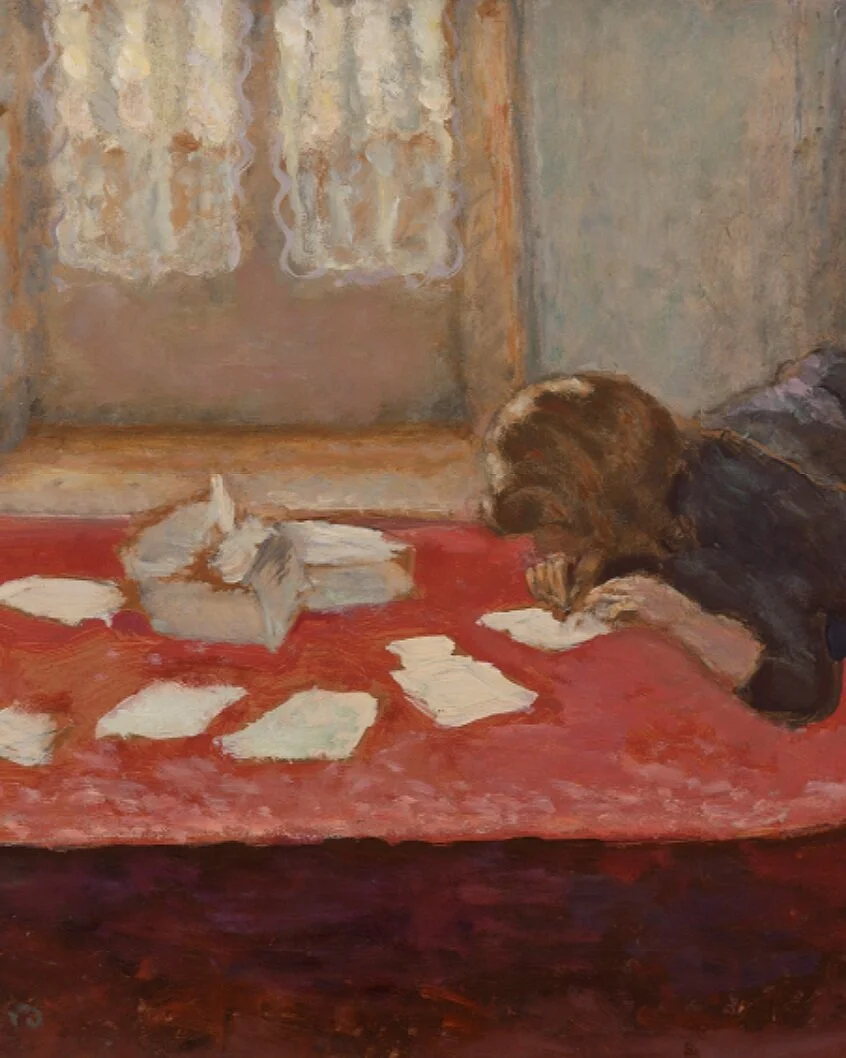

Pearlescent grey light streams through the window in this daytime scene in Paris. Wavy, linear brushstrokes give the interior space a gauzy, atmospheric quality. The walls and furniture at the far side of the room—the armoire, wall, window, and chair—seem to melt into one another. We see an intensely focused woman seated alone at a long crimson covered table. While her actions are specific, the figure herself is largely undefined: she writes hunched over, face anonymous, hidden behind her hair. A keen sense of dislocation and intrusion pervades the scene.

Our slightly elevated vantage point accentuates the plane of the table top with its large expanse of red. The table extends both beyond the left side of the picture and horizontally across the composition. The woman and her chair complete the forefront and cut off the viewer from the rest of the room. Scattered papers across the tabletop create rhythmic punctuations across the field of red, skittering out of the picture frame on the left. As Cindy Kang, a curator at the Barnes Foundation explains, “Bonnard’s placement of the papers seems purposeful. The artist left gaps in the red tablecloth that he later filled in with saturated, urgent strokes of white paint that have a messy, impasto quality.... he conveys a sense of urgency in this ephemeral moment of daily life.” There is a tangible immediacy and intimacy to the composition, not unlike the first draft of an impassioned letter.

Young Woman Writing was painted in 1908 after the artist Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) traveled to the Netherlands, where he was inspired by seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of letter writing. A common subject of genre painting, letter writing symbolized the interior of a person, the process of capturing one’s innermost thoughts onto the page.

reflections…

Known as an Intimist painter, Bonnard presents a universe of the familiar through the lens of his own recollection. “Bathed in the afterglow of memory,” Bonnard’s compositions imbue emotionality and subjectivity to the seemingly mundane. In Young Woman Writing, the artist tenderly distills the quotidian into a muted abstraction. There is depth and richness, even mystery, to be found in the prosaic, he implies, if we slow down. The domestic interiors of the Intimist tradition compel us to take notice of the beauty of our daily rituals—“to paint,” as French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé wrote, “not the thing, but the effect it produces.”

Jason Han, MD, similarly expounds on actively absorbing the present moment in all its nuanced subtleties to glean insight from clinical encounters. “A reflection is a habit of looking at someone or something in a way that transforms a passive experience into an active, meaningful one. It is a form of alchemy that we all possess,” writes Dr. Han in The Philadelphia Inquirer. As Dr. Han advocates, how can clinicians more intentionally pause to reflect and derive greater meaning and satisfaction from everyday tasks?

There is a rich history of creative writing by physicians, from twentieth-century icons William Carlos Williams and Somerset Maugham to contemporaries such as Abraham Verghese and Rafael Campo. The application of narrative and story as tools to receive and process patient and physician experience has only recently gained solid footing in medical education. Rita Charon, MD, founder of the Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, has added depth and method to this endeavor through instruction in close reading, study of literature and other narrative forms, and reflective writing.

The woman’s intensity and focus as depicted in Young Woman Writing brings to mind the kind of immersion for which Charon advocates. How might this perspective enhance the patient-physician relationship in the clinical encounter? Novelist and narrative medicine scholar Nellie Hermann states, “Writing is, at root, an externalizing act. When we write, we bring what is inside to the outside; we put words, however indirectly or metaphorically or imperfectly, to what’s inside of us, feelings or experiences that previously were not concrete.” What do physicians stand to gain from “externalizing” our experiences into words? How might this help build a stronger sense of meaning and purpose in doctoring? Can writing be a way to strengthen empathy and connection?

sources

“Barnes Takeout: Art Talk on Pierre Bonnard's Young Woman Writing.” Youtube.com, Barnes Foundation, 15 Apr. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tfu-vZQyfR4.

Charon R, DasGupta S, Hermann N, et al. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Delistraty, Cody. “You'll Never Know Yourself: Bonnard and the Color of Memory.” The Paris Review, 15 Mar. 2019, www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/03/13/youll-never-know-yourself-bonnard-and-the-color-of-memory/.

Han, Jason. What One Resident Has Learned from Listening to Patients' Stories. The Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 Oct. 2020, www.inquirer.com/health/expert-opinions/patient-reflection-doctor-listen-20201014.html.

Illingworth, Dustin. At Home with the Intimists. Lapham's Quarterly, 17 Sept. 2018, www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/home-intimists.

“Pierre Bonnard.” Artnet, www.artnet.com/artists/pierre-bonnard/.

“Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947): The Late Interiors.” Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bonn/hd_bonn.htm.

Williams, Hannah. The Radiant Paintings of Les Nabis, the Movement Started by Bonnard and Vuillard. Artsy, 11 Apr. 2019, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-radiant-paintings-les-nabis-movement-started-bonnard-vuillard.