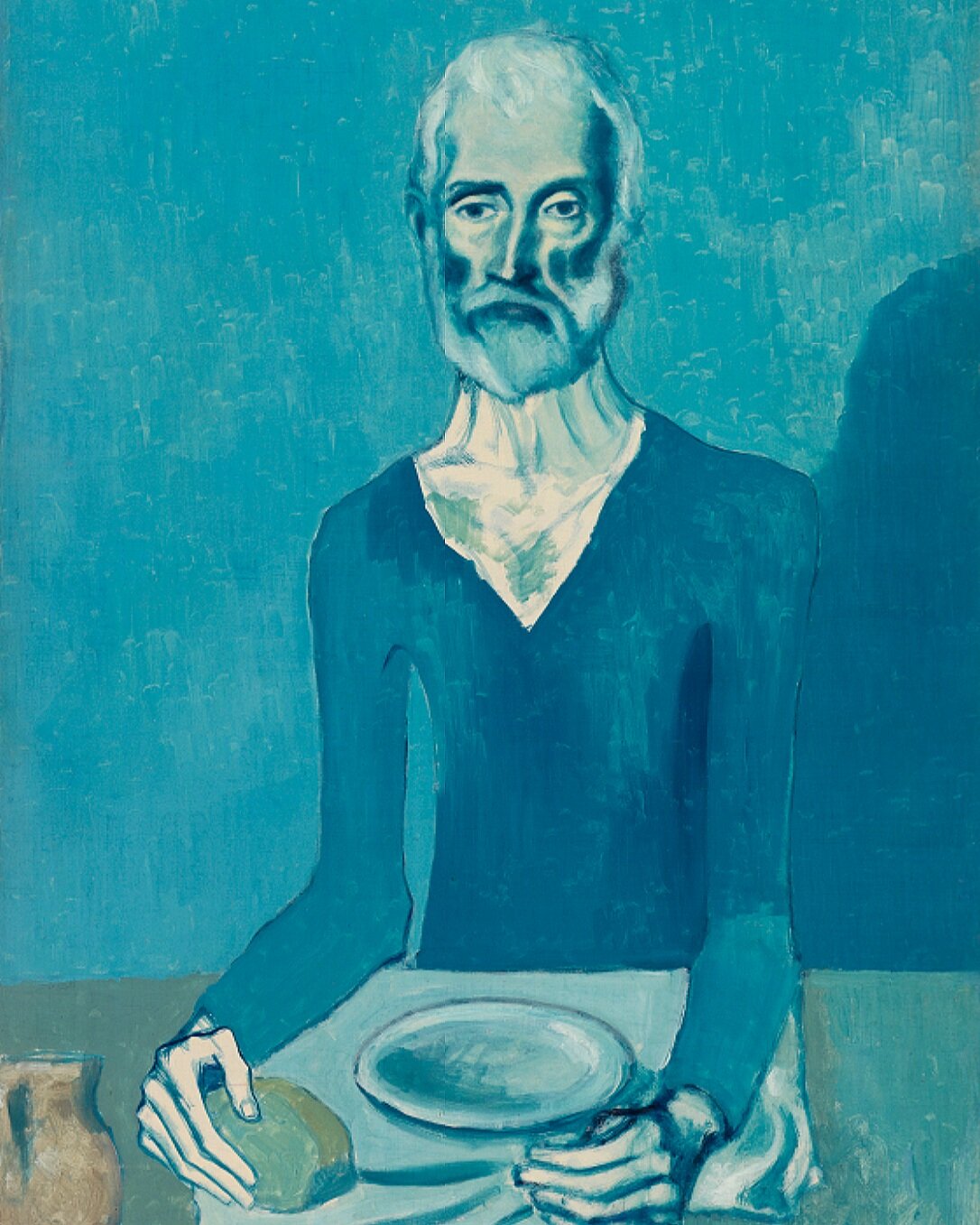

Rx 8 / The Ascetic

Pablo Picasso, The Ascetic (L’Ascète), 1903. Courtesy of Barnes Foundation

The way we die is a mirror of the way we live.

- Takumi Nakazawa

During his aptly named Blue Period, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) struggled with severe depression and grief following the death of a close friend. His resultant compositions pursued themes of suffering and alienation with somber palettes of blues, greys, and greens, often featuring the sick, blind, imprisoned, and indigent. In The Ascetic, Picasso masterfully combines artistic approaches and plastic choices that create unsettling outcomes—in particular, an unresolved combination of three and two-dimensional elements. The face, neck, and hand on right are strongly modeled in a robust three-dimensionality. Yet, the torso, arms, and hand on left are relatively unmodeled, reading as flat color areas. At far left, the back edge of the table appears pushed up against the wall, leaving the figure to reside in an extremely shallow pictorial space.

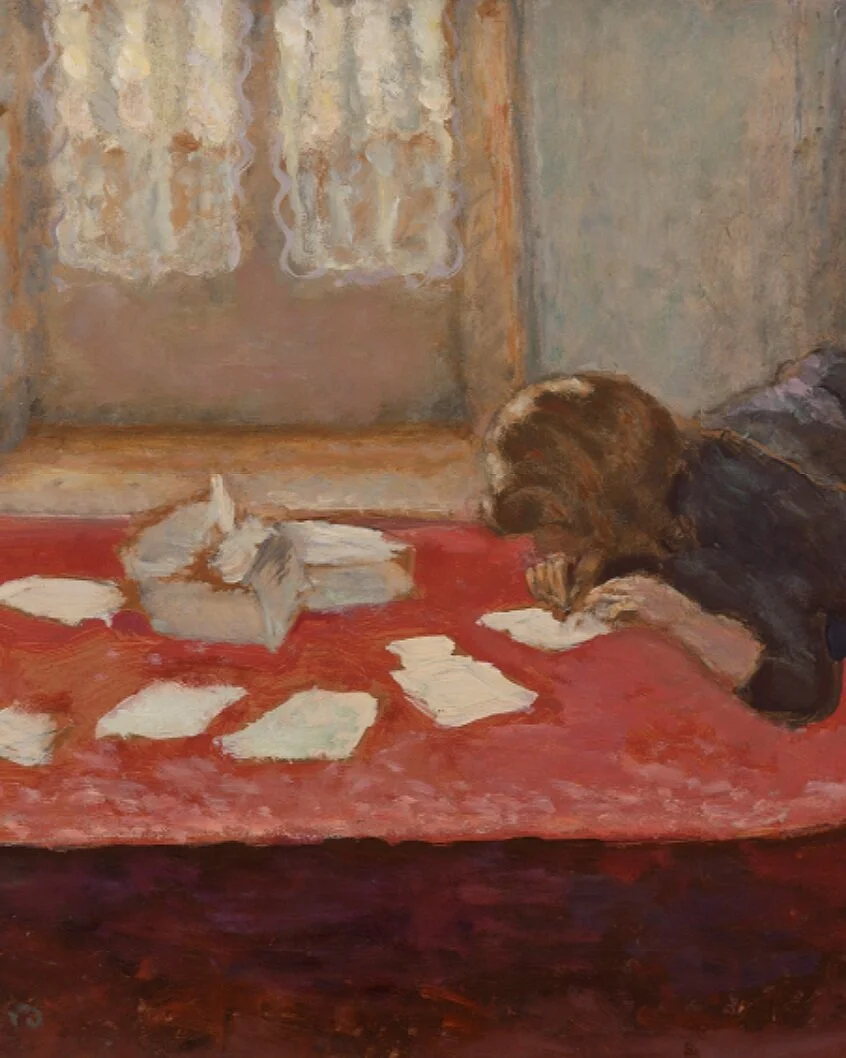

In the modern context, The Ascetic is redolent of kodokushi, or the rising epidemic of “lonely death” in a rapidly aging Japanese population. Misaligned between generations and disarticulated from communal and filial ties, many Japanese elderly living alone subsist in an interminable state of semi-absence. The post-war capitalist ‘golden age’ of Japan ushered in burgeoning industrialization and urbanization at the gradual expense of multi-generational family homes. Massive economic stagnation, a declining national birth rate and cost-prohibitive private health care have now rendered many senior citizens uncared for. In a country with one of the world’s largest geriatric populations, longevity poses a problem: quality of life.

“an unresolved combination of three and two-dimensional elements.”

The deaths of these solo-dwellers, conservatively estimated at 30,000 per year, contribute to a haunting cultural narrative of societal neglect. The bodies are discovered weeks or sometimes months later in various states of putrefaction (warmer summer temperatures hasten detection) surrounded by remnants of a life in solitude – half eaten pots of food, piles of soiled rubbish, a neglected pet. They die from starvation, self-neglect, underlying health conditions, loneliness. Predicted to peak by 2040 to approximately 1.7 million deaths with one in four occurring unwitnessed, kodokushi contests the meaning of home and the “ethics of dwelling.” (Zigon, 2014) While these statistics may be unique to Japan, the concept of kodokushi extends globally to our care of the elderly and how we conceive of the responsibilities and obligations of family and communities.

reflections…

Both The Ascetic and kodokushi speak to the prevalence of loneliness and dis-belonging in capitalist societies, and the ways in which the value and dignity of individual lives is often denied. In response to this existential plight of “ordinary suffering” (Das, 2016), many elderly in Japan have chosen to preemptively self-alienate, in order to avoid burdening others with their eventual dependency.

Is choosing to be alone and perhaps even embracing it simply an unavoidable byproduct of modernity, or an example of a ‘relationless’ paradigm when the social institution of family is no longer considered an inherent good? In what ways do physicians bear witness to variations of this narrative of loneliness in the clinical encounter? How can we remain mindful of the psychological burden and pain of dis-belonging in its myriad forms as it pertains to the patients and communities we care for?

How do we better define the ethics and ecology of care, the meaning and value of connectivity and belonging, and the repercussions of social abandonment as it pertains to the elderly, the disabled, the vulnerable, and public health more broadly? How has this become particularly apparent during the COVID pandemic? As clinicians, what is our role in mobilizing and proactively leading our communities to build more caring, socially responsible relationships amongst one another?

sources

Bremner, Matthew. “In Aging Japan, Dead Bodies Often Go Unnoticed for Weeks.” Slate Magazine, 26 June 2015, slate.com/news-and-politics/2015/06/kodokushi-in-aging-japan-thousands-die-alone-and-unnoticed-every-year-their-bodies-often-go-unnoticed-for-weeks.html.

Danely, J. (2019), “The Limits of Dwelling and the Unwitnessed Death.” Cultural Anthropology, 34: 213-239. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca34.2.03.

Das, Veena, and Clara Han, editors. Living and Dying in the Contemporary World: A Compendium. 1st ed., University of California Press, 2016. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv1xxwdf.

Gotthardt, Alexxa. “The Emotional Turmoil behind Picasso’s Blue Period.” Artsy, 13 Dec. 2017, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-emotional-turmoil-picassos-blue-period.

Onishi, Norimitsu. A Generation in Japan Faces a Lonely Death. The New York Times, 30 Nov. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/11/30/world/asia/japan-lonely-deaths-the-end.html.

Zigon, Jarrett 2014 “An Ethics of Dwelling and a Politics of World-Building: A Critical Response to Ordinary Ethics.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 20, no. 4: 746–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12133.