Rx 9 / The Gross Clinic

All I was trying to do was to picture the soul of a great surgeon.

- Thomas Eakins

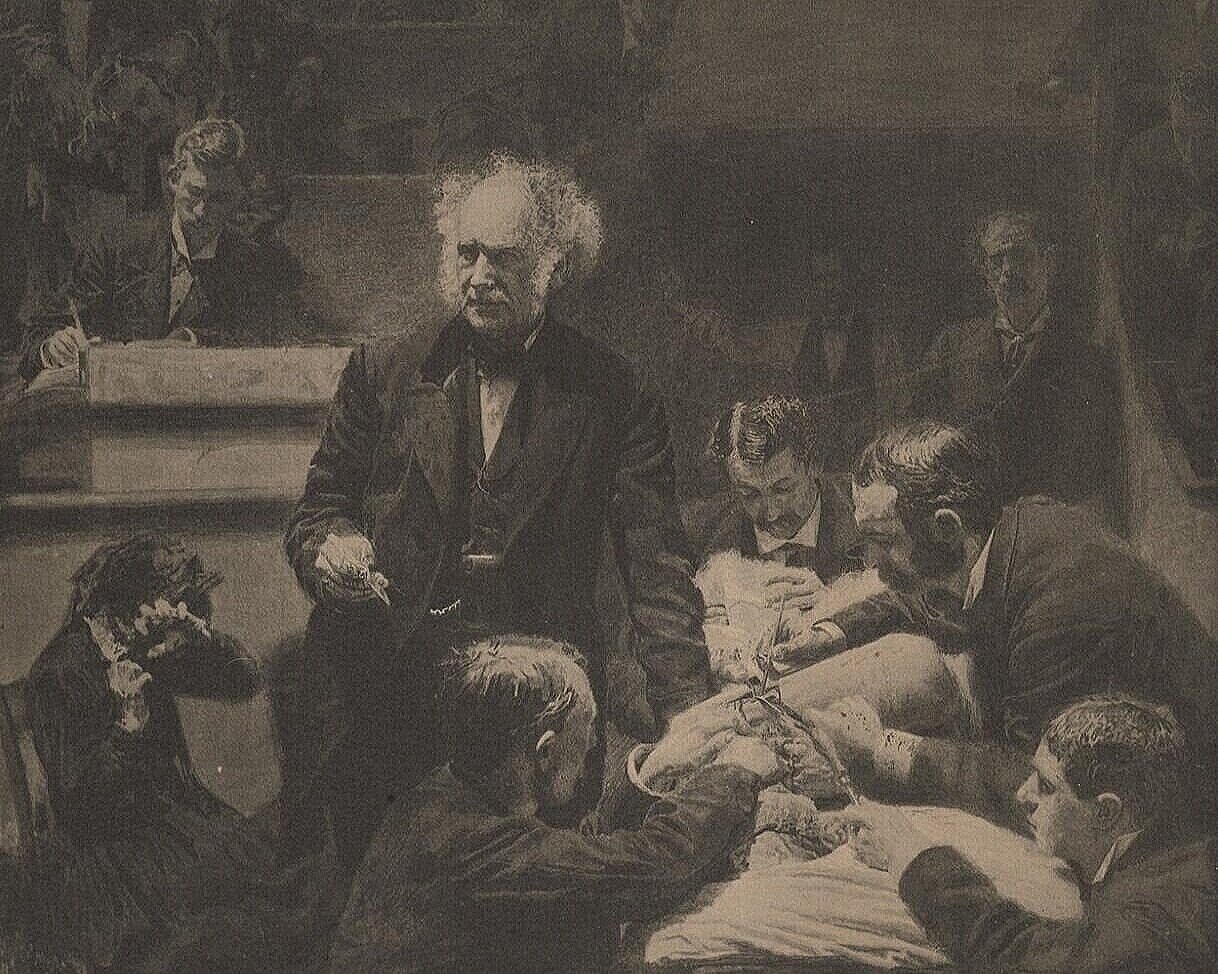

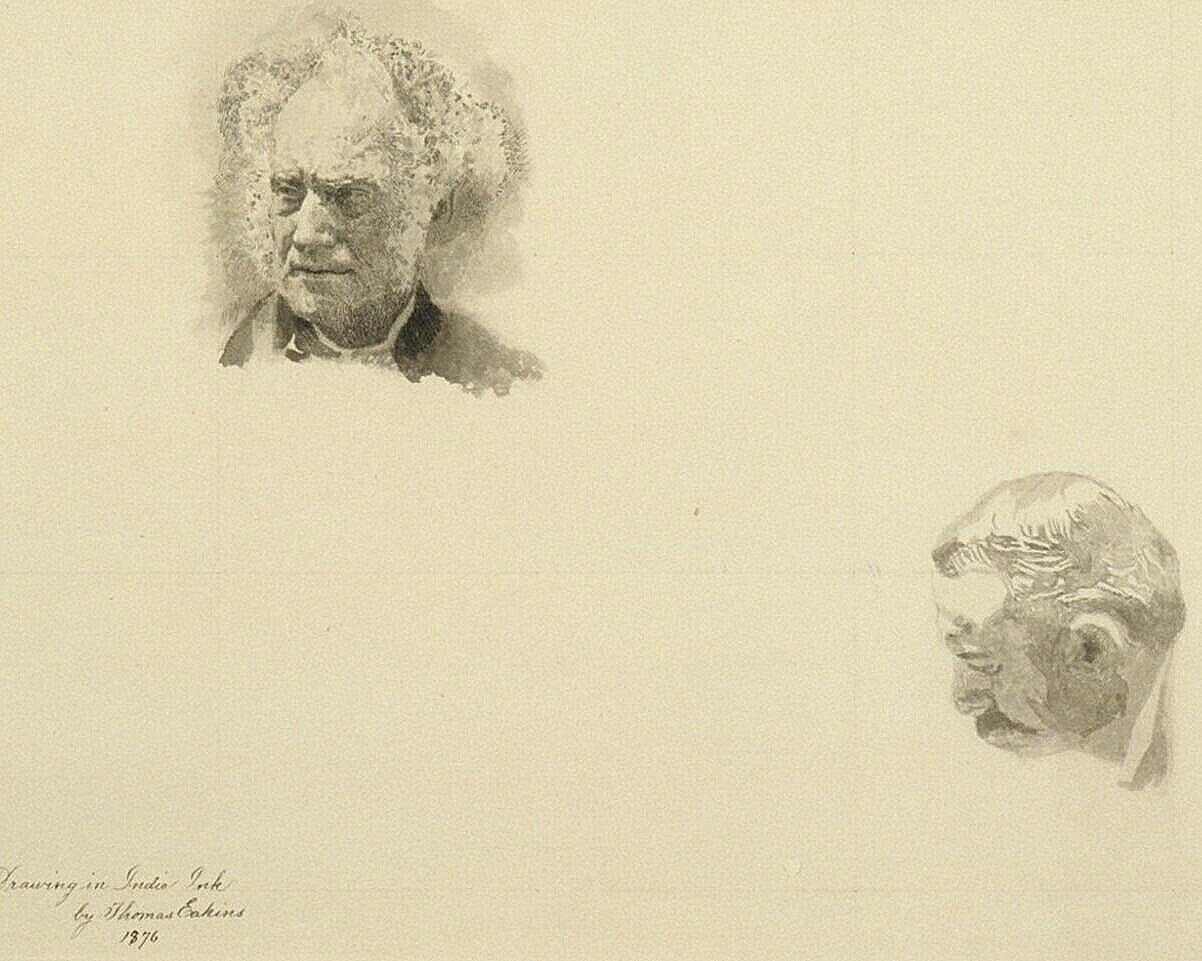

Standing tall and center in Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic is Dr. Samuel Gross, an internationally esteemed surgeon and one of the first graduates of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. In the nineteenth-century surgical amphitheater of Jefferson Medical College, a surgical team treats osteomyelitis of the femur, a severe bone infection, with a technique pioneered by Dr. Gross. Bloodied scalpel in hand, Gross slightly angles his stance to lecture medical students seated in the rafters. Known as “the emperor of American surgery,” Gross seems beatified with sunlight streaming through a skylight above. (Surgeries like this were only possible during daylight.)

To the left of Gross, a distressed woman—comparatively dwarfed in stature, traditionally presumed to be the patient’s mother—recoils in horror with clawed hands and a burrowed head. Identifiable features of the patient on the table are similarly obscured by the anesthesiologist’s chloroform cloth, exposing only a mound of milky flesh for the procedure. Eakins strategically uses red to draw the viewer’s eye from the opened leg of the patient, to the scalpel in Gross’s hand, to the pencil held by a medical student in the gallery just above the surgeon’s right shoulder. The glowing red light in the tunnel behind Gross brings the eye full circle and leads to Eakins himself, cast to the right of the tunnel railing, sketching or drawing.

The Gross Clinic was created just prior to aseptic surgical technique. The day’s sanitary practices are accurately represented: bare hands, no masks, overcrowding of the surgical table, no white coats or gowns. In stark contrast, Eakins’s later work, The Agnew Clinic (1889), highlights clean linens and adherence to sterility, demonstrating a growing awareness of bacteria and infection. While Gross never published his postoperative infection rates, general reported mortality in late nineteenth-century Philadelphia was a staggering twenty-five to thirty percent for infected amputations.

“GROSS SEEMS BEATIFIED WITH SUNLIGHT.”

From the late-eighteenth century, Philadelphia was regarded as one of two epicenters (the other was Edinburgh) of education for physicians and surgeons. A Philadelphia native, Eakins understood the vitality and excellence of his hometown’s scientific community. He completed The Gross Clinic in time for Philadelphia's 1876 Centennial Exhibition to solidify the city’s presence on the international medical stage. The unveiling of the piece was ensconced in controversy, with critics and viewers alike lashing out at the “powerful, horrifying” and inartistic subject-matter. While ultimately rejected for display, The Gross Clinic is now regarded as an invaluable artifact of Philadelphia medical history and one of Eakins’s most ambitious works.

REFLECTIONS…

Consider the striking contrast between Dr. Gross and the female figure. What do their scale of size and body language symbolize, in relation to the other? Did Eakins purposefully juxtapose them to embody a deeper existential struggle? Are rationality and emotionality at odds with one another in the acute clinical setting?

In the spring of 2017, The New Yorker cover featured four female surgeons’ faces as seen from the perspective of a patient lying down in the operating room. A social media #ILookLikeASurgeon whirlwind ensued, garnering hundreds of posts from surgeons around the globe. Dr. Susan Pitt, endocrine surgeon who spurred the trend: “Women surgeons are saying to other women surgeons, ‘I see you,’ and to the world, ‘See us.’”

Does Eakins’s portrayal of Dr. Gross typify a historical or modern perception of the surgeon, or both? How does The Gross Clinic contribute to a visual, oral, and written culture of hyper-masculinity and hierarchy? (Logghe, 2018) What are potential ethical harms of propagating the surgeon stereotype with respect to gender, racial or ethnic minorities in medicine? How might the surgeon stereotype exert influence on the patient-physician dynamic or a patient’s behavior?

Courtesy of Dr. Victoria Gershuni, Penn Medicine.

sources

“Fact Sheet: The Gross Clinic.” PEW, 21 Dec. 2006, www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2006/12/21/fact-sheet-the-gross-clinic.

Friedlaender, Gary E., and Linda K. Friedlaender. “Art in Science: The Gross Clinic by Thomas Eakins.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, vol. 472, no. 12, 15 Oct. 2014, pp. 3632–3636, 10.1007/s11999-014-3989-8.

Jones, Jonathan. “The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins (1875).” The Guardian, 3 Aug. 2002, www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/aug/03/art.

Logghe, Heather J., et al. “The Evolving Surgeon Image.” AMA Journal of Ethics, vol. 20, no. 5, 1 May 2018, pp. 492–500, journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/evolving-surgeon-image/2018-05, 10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.5.mhst1-1805.

“The Medical Story behind Thomas Eakins’ Gory Masterpiece.” PBS NewsHour, 11 Nov. 2018, www.pbs.org/newshour/health/the-medical-story-behind-thomas-eakins-gory-masterpiece.

Mouly, Françoise. “The New Yorker Cover That’s Being Replicated by Women Surgeons Across the World.” The New Yorker, 11 Apr. 2017, www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-new-yorker-cover-thats-being-replicated-by-women-surgeons-across-the-world.