Rx 18 / L'Ange anatomique

How can the free gaze that medicine, and, through it, the government, must turn upon the citizens be equipped and competent without being embroiled in the esotericism of knowledge and the rigidity of social privilege?

—Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic (1963)

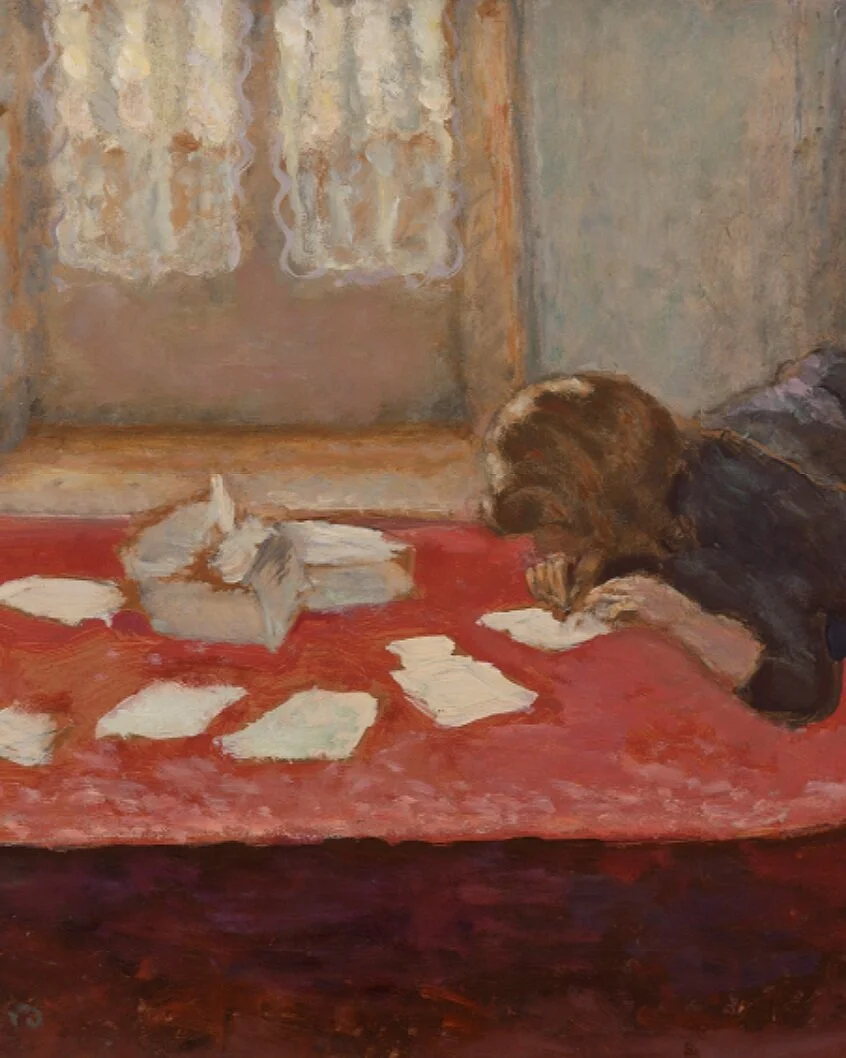

In this mezzotint print known as L’Ange anatomique or The Flayed Angel, a woman’s body unfolds like wings as she demurely looks on. Seated as if posing for a portrait, she transforms from artistic sitter to anatomical specimen with exquisitely rendered bone and musculature. Muscles of the Back was featured in French Enlightenment anatomist Jacques-Fabien Gautier-d’Agoty’s notable book of human musculature, Myologie complette en couleur et grandeur naturelle, or Complete Scientific Study of Muscles in Color and Life-Size, known for its dramatic imagery and scientific accuracy.

Anatomist, painter, and printmaker, Gautier-d’Agoty pioneered the four-plate color mezzotint method seen in Muscles of the Back, an engraved steel and copper print with striking tonal pigmentation. The rich color saturation and delineation of the intercostal and paraspinal musculature is a stunning example of Gautier-d’Agoty’s precision. While this time-consuming and expensive technique fell out of favor after the French Revolution, the rapid expansion of medical education during the Enlightenment was a profitable endeavor for Gautier-d’Agoty. He abandoned mezzotint production in favor of less expensive, mass reproductions of scientific objects of interest and anatomical models for medical schools. Gautier-d’Agoty’s corporeal prints artistically meld his discipline of observation with a scrupulous pursuit of anatomic reality.

An elected member of the French Academy of Sciences, Gautier-d’Agoty engaged in prosperous partnerships with physicians and scientists, including the renowned surgeon Joseph Guichard Duverney. In fact, Gautier-d’Agoty signed Duverney’s name on every mezzotint in Myologie to acknowledge the surgeon as the ‘inventor’ of the images. The book was then dedicated to King Louis XV with the following inscription: “Your majesty would not deign to cast his eyes on these marvels from too close and affecting a distance. I present them to you faithfully printed after nature. My burin* will save you the horror that nature itself would inspire in you.”

*Steel cutting tool for engraving

reflections…

Muscles of the Back melds person and anatomical subject, as seen through the penetrating lens of a physician. We might think of this work as embodying French philosopher Michel Foucault’s notion of the “medical gaze,” in which the patient is reduced to a geography of disease and biological functions. The act of seeing in the clinical encounter thus became synonymous with visual interrogation of the body and an implicit power dynamic. How does Muscles of the Back speak to the sharp distinction between the seer and the seen?

For some contemporary medical specialties, radiology and pathology in particular, the physician functions at a high degree of abstraction, encountering a likeness or representation of the patient and rarely the patient themselves. How does this approach introduce yet another degree of separation between patients and caregivers, rendering the physician invisible to the patient and vice-versa? In turn, how does the invasiveness of Muscles of the Back enable us to visualize the patient in her entirety and yet not see her at all?

In the history of art, there is a long tradition of envisioning an elaboration of the body as mediated by technology. The Italian Futurists, for example, painted cyclists whose bodies became indistinguishable from the vehicles they rode. In Muscles of the Back, we see a body intrusively revealed and transformed, mimicking the mechanics of a medical procedure or imaging, and conjuring the notion of human-as-machine. What is the purpose of viewing anatomical dissections as works of art? As Gautier-d’Agoty implied in his inscription to the king, how does art render nature more palatable to our viewing or elevate the experience of visual consumption of the body?

sources

d'Agoty, Jacques Fabien Gautier. “Neck Muscles, Plate Three from Complete Musculature in Natural Size and Color.” The Art Institute of Chicago, Prints and Drawings, www.artic.edu/artworks/149493/neck-muscles-plate-three-from-complete-musculature-in-natural-size-and-color.

Barnett, R. The Sick Rose: Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration. London, Thames & London, 2014.

Gray, Benjamin R., and Richard B. Gunderman. “Lessons of History: The Medical Gaze.” Academic Radiology, vol. 23, no. 6, 2016, pp. 774–776., doi:10.1016/j.acra.2016.01.016.

Lowengard, Sarah. “The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe.” The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-Century Europe: Jacques-Fabien Gautier, or Gautier D'Agoty, www.gutenberg-e.org/lowengard/C_Chap12.html.

“Mezzotint – Art Term.” Tate UK, 1 Jan. 1970, www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/m/mezzotint.

“Muscles of the Back: Partial Dissection of a Seated Woman, Showing the Bones and Muscles of the Back and Shoulder. Colour Mezzotint by J. F. Gautier D'Agoty, 1745/1746.” Wellcome Collection, wellcomecollection.org/works/yec7bmwu.