Rx 21 / Last Sickness

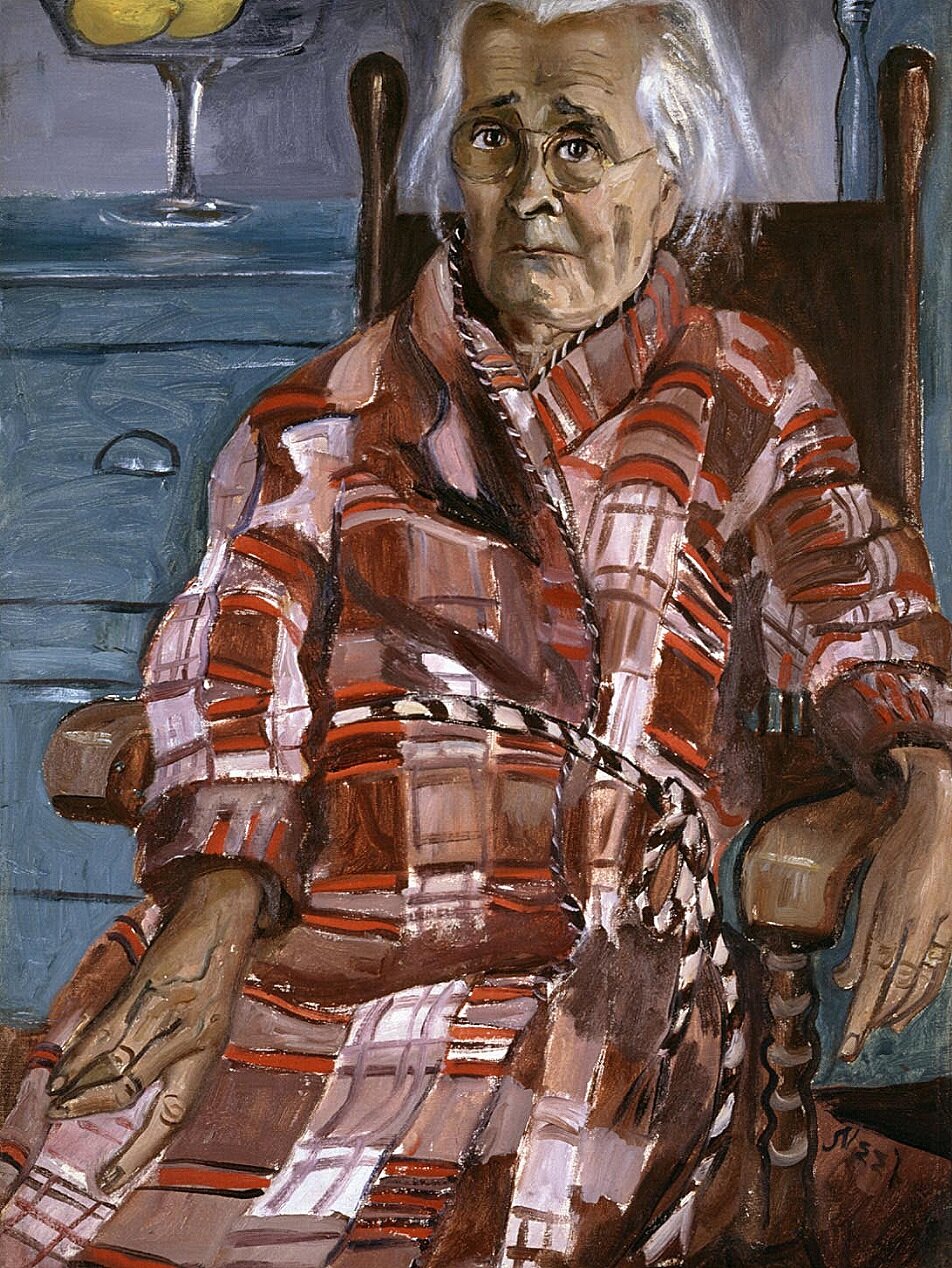

Alice Neel, Last Sickness, 1953. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

I didn’t see life as a Picnic on the Grass. I wasn’t happy like Renoir.

- Alice Neel, 1921

Last Sickness is one of four portraits that Alice Neel painted of her ill mother, Alice Hartley Neel, while they lived together in New York, completed a few months before her mother’s death in 1954. A tender mother-daughter dynamic is captured as Neel lovingly—if awkwardly—documents this encounter and renders it public. Her mother’s countenance is disarmingly wry with raised eyebrows, off-kilter eyes, and crooked glasses hinting at reluctant participation and skeptical amusement. The vibrant citrus in the background evokes youth and vitality and contrasts with the sitter’s physical resignation to the effects of time. Sagging discolored cheeks, wispy white hair, papery translucent veins, and warped arthritic joints are reminders of the body’s slow decay. Neel is both sensitive to and frank about her mother’s condition; she does not impose judgment or affectation. Rather, she invites the viewer to see her mother with dignity, and to confront old age, writ large, head on.

Born in the suburbs of Philadelphia in 1900, Neel spent her career as a shunned and iconoclastic female portrait artist in a male-dominated art scene. A socially conscious artist, she sympathized with the dispossessed at a moment when many artists favored abstraction, and was committed to visualizing real people and the plight of being female in the modern world. Neel often painted single mothers, pregnant women, the poverty-stricken, elderly, and sick, as well as supporters of the women’s movement and left-wing activists more generally. She was steadfast in depicting the world around her with compassion, acuity, and freedom. The candor and warmth of her paintings, like Last Sickness, reflect a deeply psychological approach to her sitters. With an unwavering commitment to capturing the full breadth of life in her portraits, Neel’s work offers a penetrating yet tender gaze into the human condition.

reflections…

Last Sickness is a poignant study of Neel’s mother’s final weeks and perhaps the last visual recording of her life, rendered with great care. There is a tangible intimacy even as the artist confronts her own relationship with aging, death, and dying. Painting allowed Neel to process and work through pending loss, to record memory and document relations.

Are there ways in which beautiful and thoughtfully rendered portraits and artworks can function as visual analogs of care? How can physicians humanize and overcome the oftentimes depersonalized, mechanical conditions of clinical medicine such as the electronic medical record, automated messaging, or a telemedicine visit? Beyond a medical diagnosis or history of present illness, how can physicians imbue the patient encounter with a sense of individualized care? As Neel has done, how can we more fully embrace and incorporate the arts—its portrayals of human relationships and means of representing people and their illnesses, but also joys and lived experiences—into spaces of caregiving?

In what ways does Last Sickness model a humanizing paradigm of care for the elderly and those approaching or receiving end of life care? Amid the COVID-19 crisis, how have we witnessed the emergence of a highly utilitarian and practical rhetoric regarding the “benefit-maximizing allocation” of resources, particularly at the outset of the pandemic? Could this reverberate beyond our present moment and have a lasting impact on how we value and treat our elderly and vulnerable populations, both within healthcare and society? How have the extreme circumstances of the pandemic enabled or exacerbated ageism in various forms?

sources

Aronson, Louise. “Ageism Is Making the Pandemic Worse.” The Atlantic, 28 Mar. 2020, www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/03/americas-ageism-crisis-is-helping-the-coronavirus/608905/. Accessed 16 May 2020.

"Collected souls of Alice Neel." Washington Times [Washington, DC], 12 Nov. 2005, p. B01.

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

Friend, Tad. “Why Ageism Never Gets Old.” The New Yorker, 13 Nov. 2017, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/20/why-ageism-never-gets-old.

Gördüren, Petra. “Expressive Realism in Alice Neel’s Early Work.” Alice Neel: Painter of Modern Life, pp. 32–37, www.aliceneel.com/articles/pdf/alice-neel-painter-of-modern-life-p32-37.pdf.

Kukla, Elliot. “My Life Is More ‘Disposable’ During This Pandemic.” The New York Times, 19 Mar. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/opinion/coronavirus-disabled-health-care.html.

Lewison, Jeremy, Walker, Barry, Grab, Tamar, Storr, Robert, et al. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2010. http://www.aliceneel.com/articles/pdf/painted-truths-02.pdf.