Rx 51 / The Laying of Hands

If we depend on sight—which seems to offer a frictionless domination over reality—we may avoid the pains and uncertainties of living, but we also lose our involvement with life.

— Gabriel Josipovici, Touch

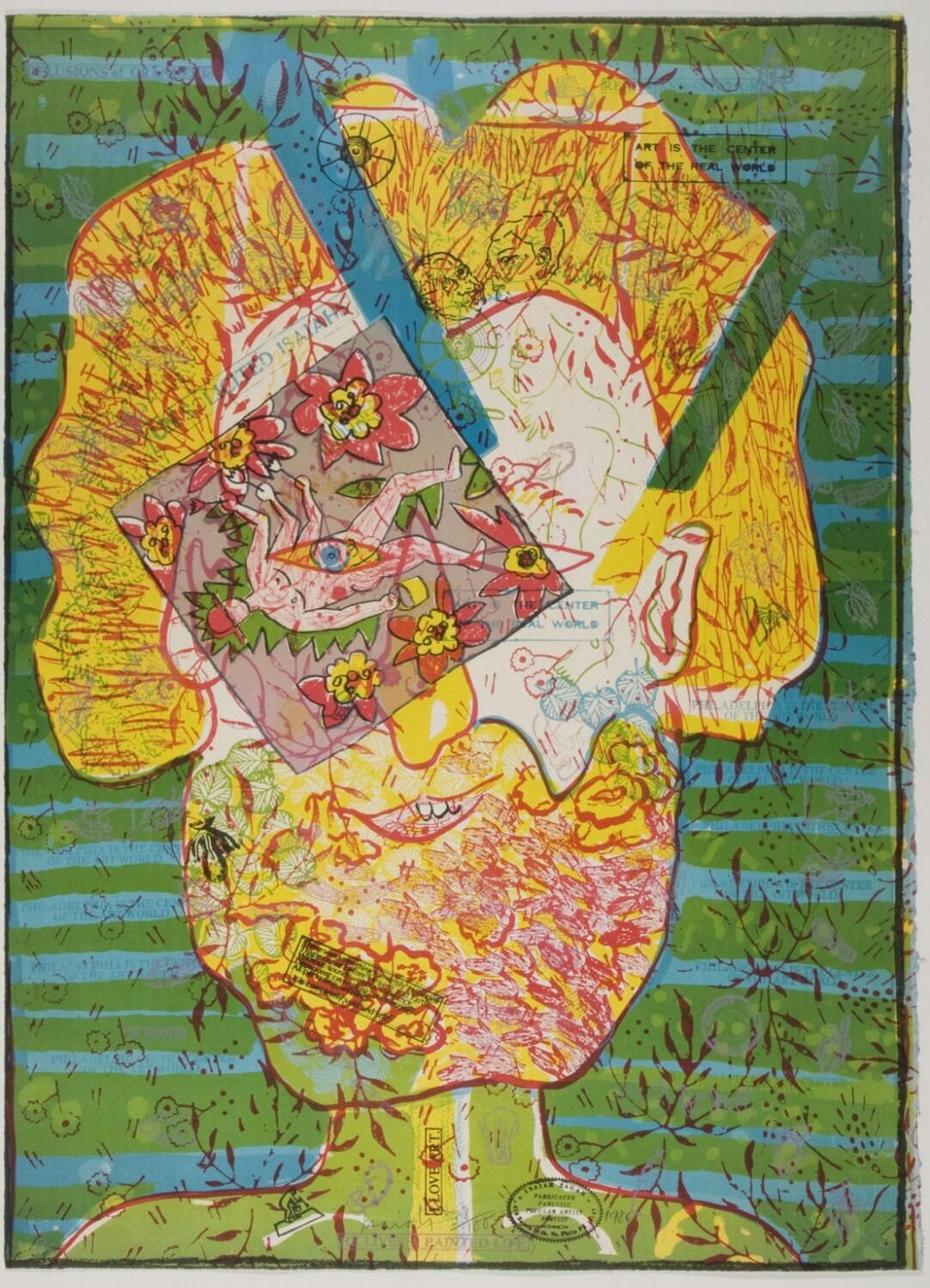

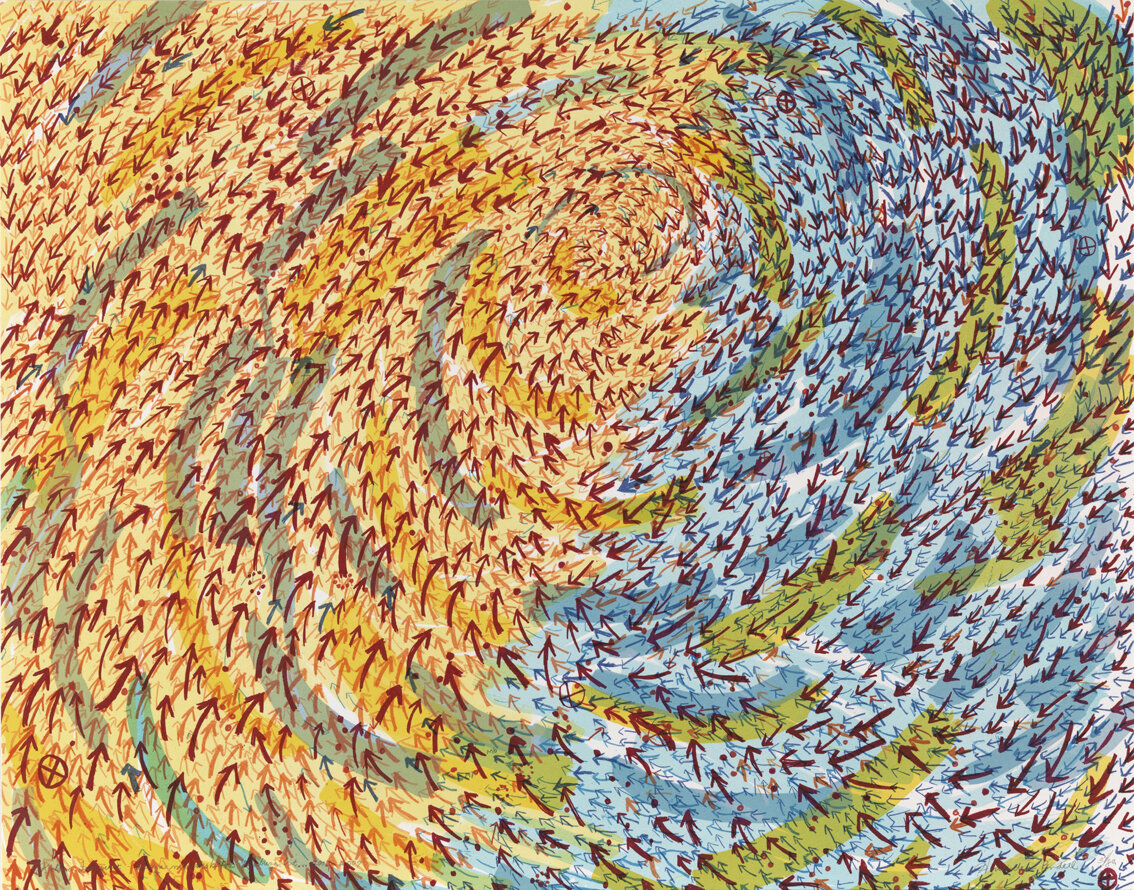

In this vibrant lithograph, blue, red, and yellow avian forms coalesce in the center, surrounded by spiraling patterns of punctuation-like forms. Blue cursive at bottom right reads, “The laying on of hands is a time honored ritual regarding the awakening of insight. Its motion is the inexorable twiness of the serpent and its wisdom is the ability to see what’s hidden in plain view.” Carefully melding textual and expressive elements, Philadelphia-born printmaker and artist Edgar Sorrells-Adewale’s (b. 1936) The Laying On of Hands is a Time Honored Ritual instantiates a ritual of its own. Notably, the handprints’ tactile relief calls to mind the iterative labor and care inherent to lithography, wherein the artist etches a design into limestone and then presses paper onto the stone. Because this print includes multiple colors, each layer would have been engraved and printed separately, overlaying atop one another to create the combination of elements we see. This “laying on of hands” may also evoke a priest or other spiritual figure who physically touches a person or object of concern in a symbolic or formal act of healing or blessing.

The Laying On of Hands exemplifies the aesthetic and ethos of the Brandywine Workshop, a center of contemporary African-American printmaking based in Philadelphia. Since its founding in 1972, the workshop has become an internationally recognized center and a vital part of the Philadelphia community. Dedicated to creating prints and to broadening the public’s appreciation of this art form, the workshop fostered such artists as Howardena Pindell, known for her intricate paintings and video art about experiences of racism; Sam Gilliam, whose painted draped tapestries are a staple of postwar abstraction; and Isaiah Zagar, whose tile mosaic murals dot Philadelphia’s South Street and feature in the city’s Magic Gardens. Brandywine’s spectrum of artistic voices and approaches to image-making was transformative for young artists of color, including Sorrells-Adewale. In 2009, the Workshop donated 100 prints, including those above, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 2012, the Museum presented the exhibition, Full Spectrum: Prints from the Brandywine Workshop, showcasing a diverse selection of works from the Brandywine’s first forty years. In the exhibition, artists explored themes such as cultural identity, political and social issues, portraiture, and landscape, as well as patterning and pure abstraction.

reflections…

Sorrells-Adewale’s handprint imagery may call to mind different acts of touch within various contexts. For some, Sorrells-Adewale’s handprint evokes the “time honored rituals” of spirituality. For others, its imprint might remind of the tactile nature of printmaking—a physical medium of text and image production that persists in a digital age. And for the clinician, the handprint summons the diminished element of touch in the clinical encounter, where computerization has all but estranged providers from the bedside. Instead of “the laying on of hands,” we have grown to rely on laboratory results and imaging studies, paradoxically seeing a patient who exists more so in their chart or on a monitor than in their body.

In his New England Journal of Medicine article, Dr. Abraham Verghese expounds on the primacy and ritual of touch within the clinical encounter: “Patients recognize how the perfunctory bedside visit, the stethoscope placement, through clothing, on the sternum like the blessing of a potentate’s scepter, differs from a skilled, hands-on exam. Rituals are about transformation, and when performed well, this ritual, at a minimum, suggests attentiveness and inspires confidence in the physician. It strengthens the patient-physician relationship and enhances the Samaritan role of doctors — all rarely discussed reasons to maintain our physical-diagnosis skills.”

Indeed, a physician’s laying of hands on the patient is inextricably tied to healing, skilled touch rendering the clinical encounter fundamentally intimate and attentive. Similarly, in Sorrells-Adewale’s lithograph and the Brandywine Workshop, the care and time afforded to print production derives from tactility and ritual. In an era where touch has become distanced—and especially in a pandemic that has changed our relationship to tactility—how do we reintroduce touch as a transformative, ritualistic component of the clinical encounter? Just as the trace of the handprint registers in this work, how can we similarly imbue patients with the comfort of having been seen and touched with care?

sources

Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Full Spectrum: Prints from the Brandywine Workshop: September 7, 2012 - November 25, 2012,” https://philamuseum.org/exhibitions/2012/755.html.

Brandywine Workshop and Archives. “Our History,” https://brandywineworkshopandarchives.org/history-and-achievements/.

Verghese A. “Culture shock--patient as icon, icon as patient.” N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 25;359(26):2748-51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0807461.