Rx 52 / How to Get Started

There is nothing more attractive and convincing than spontaneity … Most of us can observe at least moments of our own spontaneity which are at the same time moments of genuine happiness. Whether it be the fresh and spontaneous perception of a landscape, or the dawning of some truth as the result of our thinking, or a sensuous pleasure that is not stereotyped, or the welling up of love for another person — in these moments we all know what a spontaneous act is and may have some vision of what human life could be if these experiences were not such rare and uncultivated occurrences. — Erich Fromm

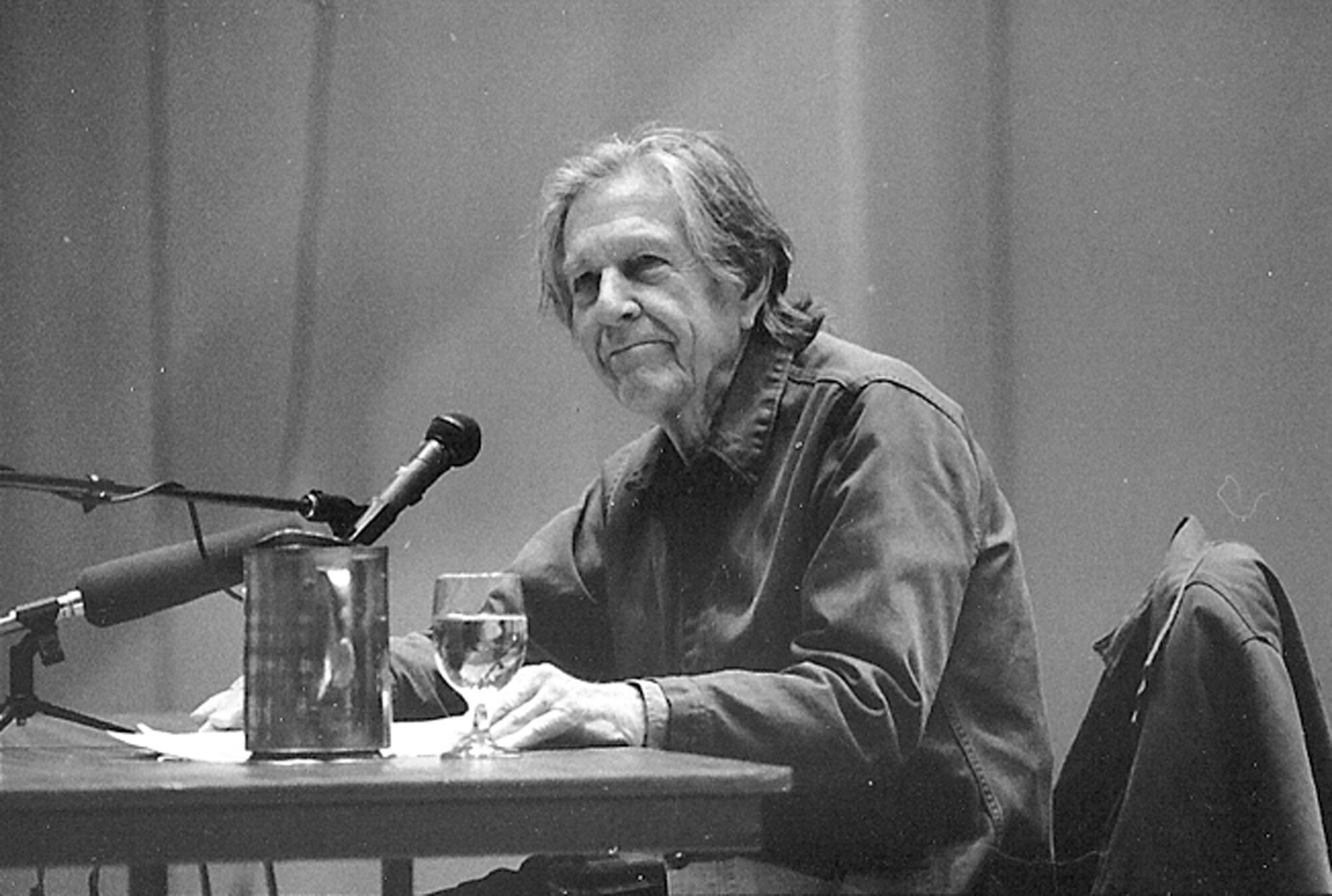

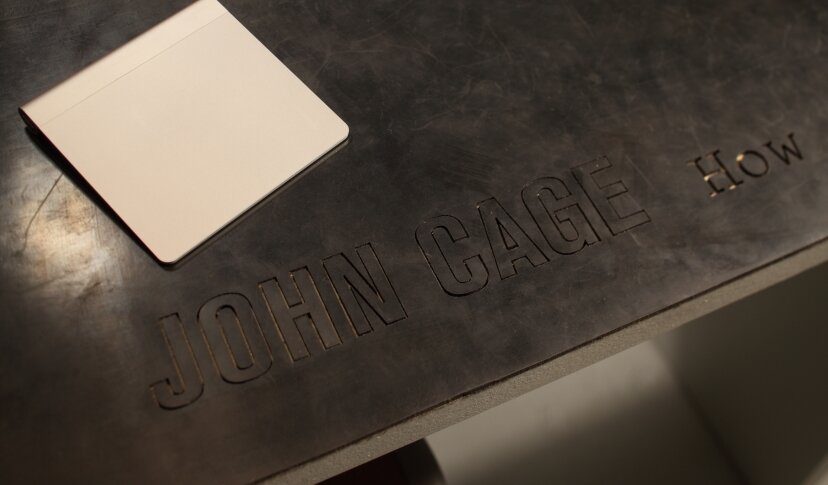

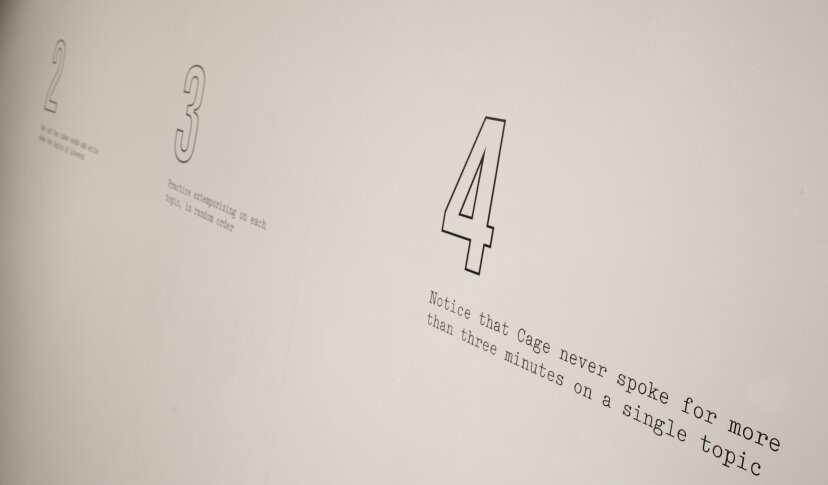

John Cage conceived How to Get Started almost as an afterthought. Minutes before going on stage at a 1989 sound design conference on director George Lucas’s ranch in Nicasio, California, the avant-garde composer abandoned his planned performance. What he chose to do instead is a performance entitled How to Get Started, wherein he extemporized, in random order, on ten topics of interest such as silence, harmony, and time, each for a maximum duration of three minutes. Each of these extemporizations was captured on tape, and then played back sequentially, in ever-increasing density. The piece thus grows in complexity from start to finish, so that at the end, the audience hears ten thought pieces simultaneously. The performance allowed Cage to reflect on the difficulty of initiating a creative process and the meaning of failure.

Cage rose to prominence during and following World War II, finding community first among the European modernists who fled to the United States during the war and later in a post-war counterculture scene. Because of his commitment to sonic abstraction, Cage is often understood as the musical counterpart to a painterly avant garde in the visual arts. In the 1950s and 60s, he began experimenting with “chance procedures,” or events that transpired by happenstance during a performance. In his most famous composition, 4’33’’, Cage elides all instrumentation and vocalization in favor of whatever ambient sounds happen to transpire for four minutes and thirty three seconds. These sounds, then, constitute the work’s score. Cage’s interest in delegating creativity to chance procedures coincided with his anarchic artistic tendencies. “The intention,” he explains in How to Get Started, “is to build up an orchestra one by one, so that gradually they will realize that they can get along without the conductor.”

In How to Get Started, Cage externalized a dialogue with himself before a live audience, clearly experimenting with a process of thinking and talking in public. In so doing, he realized that the audience became a participant who completed the work. This meant, as he wrote, “that the work takes as many forms as we are.” Because of his open-endedness about the possibilities of the creative process, Cage was a foundational figure who inspired a generation of artists to embrace risk and experimentation. As Laura Kuhn, Director of the John Cage Trust wrote, “Cage’s presentation was fully expressive of an adage by which he lived: If you find yourself in a situation in which you feel dissatisfied, the appropriate thing to do is not to criticize, which is the purview of the critic, but to identify what it is you think you don’t like, and then make something new in ‘constructive response.’ Which is, of course, the purview of the artist. But it was also emblematic of Cage’s life-long devotion to that which is truly experimental, since at the seasoned age of 76, just three years shy of his death, he continued to question his actions and choices, to listen to others and to create new ‘constructive responses,’ and to strive always to take himself, and those around him, into surprising, unknown places and experiences.”

reflections…

Twenty years after Cage’s first and only performance of How to Get Started in Nicasio, California, the John Cage Trust and Slought in Philadelphia created an interactive installation enabling the public to extemporize as Cage did—for anyone to be an artist. Today, visitors to Slought can write down ten topics of interest on a notecard and record themselves talking, each topic overlaid with those before it. Although participants speak to their own experience and create a wholly new work of art, they do so in the same model as—and in the shadow of—Cage’s first performance.

What can we learn by engaging in experimental and discursive exercises like this? How can intentional creative practice, whether through spontaneous acts, however big or small, or the arts and humanities more generally, foreground vulnerability and presence as key elements of caregiving and forging connection? How might it lead to more thoughtful ways of thinking, working, and healing?

Although much of medicine and surgery seems to rely on strict routines and preparation, Cage teaches us that there is always an element of chance in any performance or clinical encounter. Mastery of performance, then, is not about having or memorizing scripted instructions, but rather, when faced with unpredictable factors, the ability to adapt. Surgeons, similarly, may step into the operating theater, having prepared for a very specific sequence of events. Yet every surgery or clinical encounter is itself a chance procedure, a continuous mediation of order and randomness.

How can physicians, like Cage, learn to “abandon the script” and embrace the indeterminate? To what extent are standard trainee and clinician experiences such as team rounds and oral board examinations also akin to chance operations? How might improvisation cultivate a greater creative capacity within clinicians, whose work is not often regarded as creative? How can the arts and humanities strengthen one’s tolerance for spontaneity in both professional and personal realms and become a wellspring for thriving and well-being?

sources

Fromm, Erich. (1941). Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

Kuhn, Laura, Aaron Levy, and Arthur Sabatini, “How to Get Started,” Slought Foundation, 2009, https://slought.org/resources/how_to_get_started.

Kuhn, Laura, Aaron Levy, and Arthur Sabatini. (2009). John Cage: How to Get Started. Philadelphia: Slought Books.