Rx 1 / While I Breathe

Some years ago, commenting on his work about mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, the photojournalist W. Eugene Smith stated, “To cause awareness is our only strength.”

— Preface, Breath Taken

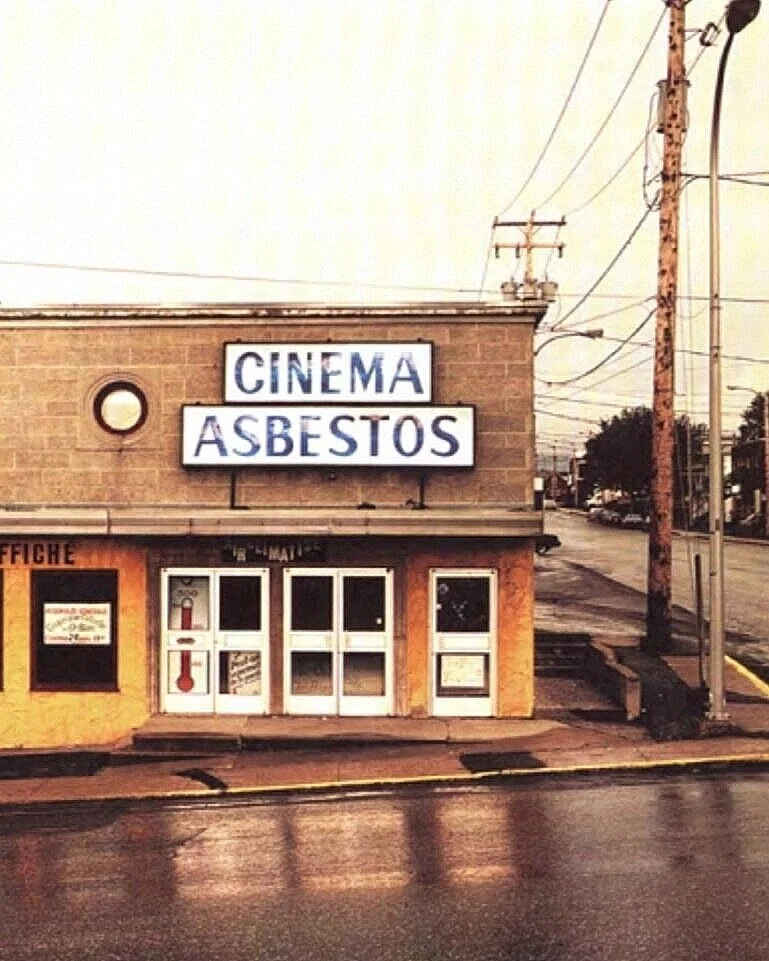

Once home to one of the largest asbestos mines in the world, Asbestos, Quebec, declined alongside its namesake industry. In the photo above, a flat, sepia-toned building set against an overcast sky reminds us of the material’s invisible and devastating pervasion: we see it in the name of the cinema and imagine it in the sheen of the pavement and the cement walls of the building. Toxicity is inescapable in this place and so many others, the right to breathe almost entirely foreclosed. If the photograph’s banality mimics the claustrophobia of life in the post-industrial town, it also reminds us of the lack of corporate accountability and failings of government regulation, which have cumulatively led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

Asbestos, derived from Greek asbestos meaning inextinguishable or unquenchable, was once a ubiquitous construction and manufacturing material, valued for its indestructible physical properties. However, as early as the 1920’s, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics published insurance reports of unusually early deaths in American asbestos workers. Those who worked directly with asbestos-containing materials—and their family members—were at significant risk of inhaling the thin silicate filaments and developing mesothelioma, an invariably fatal cancer. Many insurance companies then refused to issue life insurance policies to asbestos industry workers. Lawsuits filed against some of the largest asbestos companies in the nation led to a decades-long cover-up of a “national public health disaster of unparalleled magnitude.”

Artist and activist Bill Ravanesi’s Breath Taken: The Landscape and Biography of Asbestos (1991) catalogues the immense scale of tragedy and suffering inflicted by the North American asbestos industry. Ravanesi’s own father, Anthony, died from mesothelioma in 1981 after working in Boston shipyards during World War II. Despite its ongoing existence on the order of thirty million tons in buildings, automobiles, and water pipes, Ravanesi believes the danger of asbestos has largely and inexplicably fallen out of our collective consciousness. Through an immersive assemblage of visual and oral narratives, industry advertisements, contemporary and vintage images, and objects, Breath Taken creates “a landscape of awareness” that is both a memorial to those lost and a platform for environmental justice.

reflections…

The right to breathe seems at first glance foundational to life, and yet is continually jeopardized by innumerable health crises, including asbestos, lead contamination, and, as has become more recently visible, COVID-19 and police violence. What can we do to better protect the right to breathe? How can it become everyone’s burden?

As Ravenesi’s project demonstrates, art can play an essential role in bringing awareness to seemingly invisible public health crises. How does the longitudinal duration of a public health crisis like asbestos render it seemingly insurmountable? How can art help us make sense of the massive scale of these health crises, and one’s place within them?

Known national public health disasters of unparalleled magnitude like today’s COVID-19 pandemic are often racially and economically determined. The slow violence of longer-term epidemics such as lead or asbestos, which continue to disproportionately contaminate at-risk communities, have been further exacerbated by contemporary deregulation efforts. How can we both acknowledge and contest the insidious ways in which racism continues to predispose certain populations to repeated exposure, and lend medical expertise to activists and community groups who are advocating for health justice today?

sources

“Asbestos-Related Lung Diseases.” National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/asbestos-related-lung-diseases.

Austen, Ian. “In a Town Called Asbestos, a Plan to Restart the Industry That Made It Prosperous.” The New York Times, 3 Feb. 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/02/04/business/04asbestos.html.

“Breath Taken: The Landscape and Biography of Asbestos".” Fundclas, fundclas.org/en/breath-taken-the-landscape-and-biography-of-asbestos/.

Ravanesi, Bill. Breath Taken: The Landscape and Biography of Asbestos. Boston, Center for Visual Arts in the Public Interest, 1991, slought.org/media/files/s575-1991-00-00-breathtaken.pdf.

Socolar, D. “Breath Taken: Exposing the Ongoing Tragedy of Asbestos.” Health PAC Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 4, 1990, pp. 4–12, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10109326.

Teichman, Ronald. “Breath Taken: The Landscape and Biography of Asbestos.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, vol. 34, no. 1, 1 Jan. 1992, p. 75,journals.lww.com/joem/Citation/1992/01000/Breath_Taken__The_Landscape_and_Biography_of.20.aspx.