Rx 28 / Love Letter

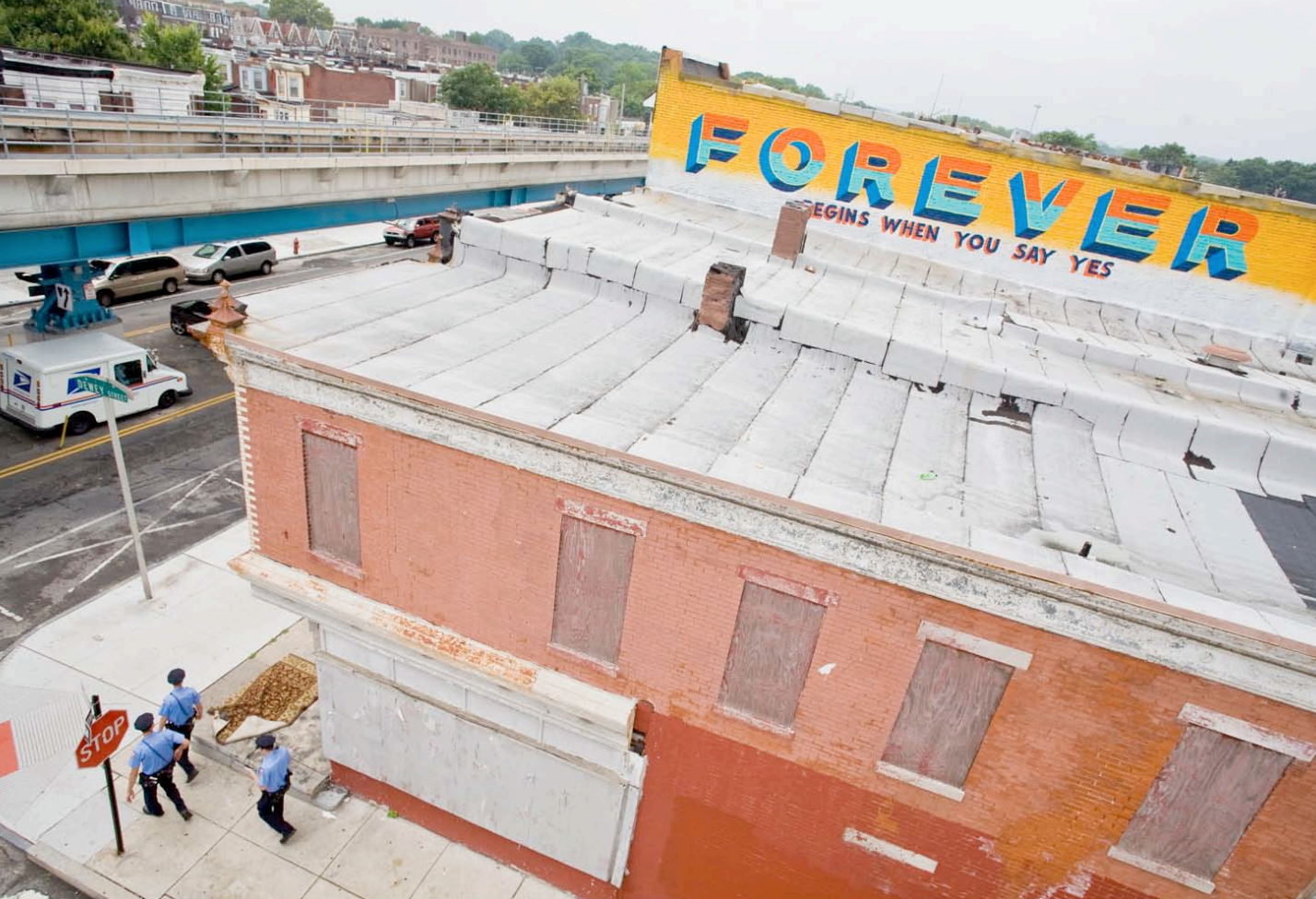

Steve “ESPO” Powers, from Love Letter series, 2009. Courtesy of Slought Foundation.

The amazing thing about graffiti is that it exists to market only itself. You see something in a place where it doesn’t belong - your mind starts to wonder as to how it got there, who was that person and what motivated them to climb that rooftop to do that thing, to make it beautiful, to avoid the law, to avoid being seen, to get down from the roof, to get back to their house safe and sound ... you’re seeing an adventure. And it’s not a Kool-Aid ad, it’s not a cigarette ad, it's something that’s giving you strength and life and vitality and it’s telling you something about the length that people will go to to make you aware that they’re there.

- Stephen Powers

Best viewed from SEPTA’s elevated Market-Frankford rail line, Love Letter is an iconic mural project adorning 50 rooftops and walls across West Philadelphia. Here, an enlarged painted Post-it at 4915 Market disrupts the urban landscape, otherwise inundated with banal corporate advertising. Instead of imploring viewers to “buy,” this mural asks them simply to “remember.” Spanning 45th to 63rd Streets, each unique, massive “love letter” delivers uplifting, pithy, even sentimental declarations in bold, large-scale typography and punchy colors. As it snakes around storefronts and residential facades, Love Letter’s visual language variously recalls 1950s vernacular signage and ‘90s R&B. The sometimes-cheeky but always sentimental messages read, for example, “Miss you too often not to love you,” and “Meet me on fifty-second, if only for fifty seconds,” the latter a reference to the 52nd Street retail corridor. Love Letter foregrounds love—between lovers, an artist and his hometown, residents and their community.

A former graffiti artist turned muralist, Steve “ESPO” Powers (b. 1968) used his native West Philadelphia neighborhood as an illegal canvas in his early years. Of the area’s graffiti scene in the eighties and nineties, he recalled, “People literally were painting people’s houses with express or implied permission of the residents of the house and owners of the house. So it was an army of community projects that was happening organically, without the city and local support or city and financial support from grants.” Powers went on to study at the University of the Arts and the Art Institute of Philadelphia, emerging in the 1990s scene under the alias “ESPO,” or Exterior Surface Painting Outreach, at a moment when the city of Philadelphia was focused less on muralism than “beautification” and anti-graffiti efforts.

In 2009, when the City of Philadelphia’s Mural Arts project commissioned Love Letter, Powers pivoted from illegal graffiti writer to grant-funded muralist. This transformation hinged on a recognition that formal structures of institutional power were necessary to gain legitimacy for himself and the team of young graffiti writers hired to execute the project. Love Letter, then, draws attention to the contrast between public art that is criminalized and considered undesirable (graffiti) and that which is sanctioned and embraced by those in power (murals and other forms of public art). Likening his art to public service and reclamation, Powers renders visible the sentiments and ethos of a community through an empowering visual lexicon. Love Letter, to Powers, is “a letter for one, with meaning for all.”

reflections…

Love Letter murals offer momentary, if recurrent, encounters, meant for commuters on the El—whether suburbanites passing through, or West Philadelphians traversing their own neighborhood. By taking advantage of these ephemeral moments, Powers creatively repurposes time and perspective with artworks seen on the way to somewhere else.

In spaces of caregiving, how can we become more cognizant of the ways in which patients and visitors experience the passing of time? Are there similar opportunities to reimagine and repurpose routine, empty or anxiety-filled periods—the time, for example, spent in impersonal waiting rooms, or a patient holding area before a procedure— by intervening with artworks that offer reflection, education, and healing?

Encountering art in unexpected places can elicit joy. At the same time, works such as Love Letter remind us these experiences can and should be empowering, transformative, and democratizing. Public art specifically has the capacity to thoughtfully represent and serve those who have historically been excluded or underrepresented within the cultural establishment. Artists like Powers are uniquely positioned to leverage public art as a tool for greater equity—to delight, but also to render visibility, navigate complex histories, and foster stronger communities (McDermott Altheimer, 2019). “To make you aware that they’re there,” as Powers said.

Similarly, hospitals have increasingly deployed the arts into spaces of caregiving, albeit with inconsistent consideration for the communities and spaces they are surrounded by and physically inhabit. From private hospitals like Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles housing thousands of famous works by modern and contemporary artists including Marc Chagall, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, to Harlem Hospital in New York which embarked on a nearly $400 million restoration in 2002 of 1930’s murals depicting everyday Black life, the representation and implementation of works varies widely by institution (Polgreen, 2002). The aptly named Mural Pavilion at Harlem Hospital went on to acquire an 18-paneled mahogany relief depicting the trans-Atlantic slave trade in Liberia, including the portrayal of freed slaves from America returning home. In 2017, hospital chief executive officer Eboné M. Carrington told The New York Times that Harlem Hospital “had long understood ‘the power of art’ in healing,” gesturing to the work’s portrayal of sacrifice and survival and its ongoing resonance within the community (Mays, 2017). Another example of academic medical centers supporting healing through the arts can be found in The Cleveland Clinic’s in-house arts program, Arts and Medicine Institute, which applies a “patient-centered curatorial practice [...] to lift spirits and affirm lives and hopefully comfort” (Wecker, 2019). More recently, Penn Medicine commissioned Maya Lin, the architect of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, to design a large-scale helical installation tentatively titled “DNA Tree of Life” in its new patient pavilion. Winding branches are meant to evoke the contours of the Schuylkill River and represent the connection of science to the natural world (Messinger, 2021).

These varied approaches raise fundamental questions concerning the purpose of art in healthcare settings. Who do these works represent and who ultimately benefits? Is it possible or necessary to commission public art that is universally legible as well as therapeutic, relevant, empowering, and decorative? Consider the ways in which Harlem Hospital’s murals and panels foreground cultural narratives that represent and affirm the communities they serve. How can institutions elsewhere be similarly thoughtful and creative in their curatorial selections? How should healthcare institutions curate or even uninstall works from a previous era that fail to represent the diversity of those who enter the hospital setting?

sources

“A Love Letter For You.” Mural Arts Philadelphia, April 30, 2019. https://www.muralarts.org/artworks/a-love-letter-for-you/.

“Love Letter by Steve Powers - GRANT,” May 4, 2017. https://www.pewcenterarts.org/grant/love-letter-steve-powers.

“An Ethics of No Edges - Programs.” Slought, January 29, 2021. https://slought.org/resources/an_ethics_of_no_edges.

Jackson, Candace. “Love Letter to Philadelphia.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, August 28, 2009. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203706604574374912593501466.

Mays, Jeffery C. “'Story of Sacrifice and Survival' Finds Home at Harlem Hospital.” The New York Times. The New York Times, October 24, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/24/nyregion/story-of-sacrifice-and-survival-finds-home-at-harlem-hospital.html.

McDermott Altheimer, Betsy. “Trend and Response: the Critical Issues Facing Our World-and What Public Art Is Doing about Them: Public Art Review.” Forecast Public Art, July 8, 2019. https://forecastpublicart.org/trend-and-response-the-critical-issues-facing-our-world-and-what-public-art-is-doing-about-them/.

Meier, Allison. “Testifying on the Walls: A Street Artist's Urban Love Letters.” Hyperallergic, March 21, 2014. https://hyperallergic.com/115554/testifying-on-the-walls-a-street-artists-urban-love-letters/.

Messinger, Hannah. “Penn Medicine Partners with Renowned Artist Maya Lin for Pavilion Art Installation Ahead of 2021 Opening of Hospital on Penn's West Philadelphia Campus – PR News.” – PR News, January 27, 2021. https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-releases/2021/january/penn-medicine-partners-with-renowned-artist-maya-lin-for-pavilion-art-installation.

Polgreen, Lydia. “For Post-Op, a Dose of Pop Art at a Brooklyn Hospital.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 15, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/15/nyregion/for-post-op-a-dose-of-pop-art-at-a-brooklyn-hospital.html.

Wecker, Menachem. “'Fine Art Is Good Medicine': How Hospitals Around the World Are Experimenting With the Healing Power of Art.” artnet News, August 2, 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/how-hospitals-heal-with-art-1606699.