Rx 27 / Spastic Walking

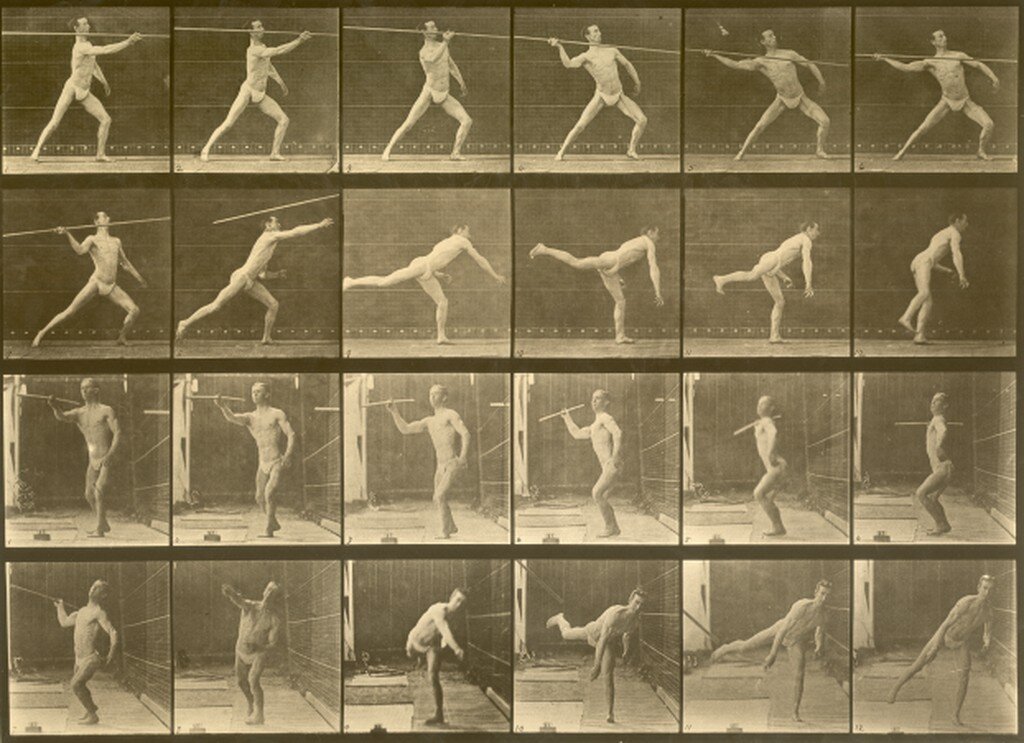

Eadweard Muybridge, "Spastic Walking," Plate 541 from Animal Locomotion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Motion, Vol. 8, 1887. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

O to quantify the nude girl guided by Matron

in the tall black dress her tonic spasm

head lolling like a half moon

jettison, jettison the stiff and stark, the tensile, taut

grid behind her to calculate tectonics

of neurons spanking the right

arm stiff as a crucifix as

detonations in my pigeon head

palm wretched up with asking for asking what

is the order inside disorder her bowl

of fire pubics man keep your eyes on

boys hooting "deadlegs, lameter, kindling . . ."

this offbeat offtick what stray virus what

yaw in the womb brought her years

of mothers gawking legs bowed beyond

O Asklepios settle the squall of sinew, be my fat moon

the scent of jacaranda on the hospital

grounds a sudden twist her long braid

swinging her bones the loyal scaffolding

swan & smooth me, gather me at different speeds, and love

this beauty this genius of flaw

- Stefi Weisburd. "Dance of the Lettuce Fan, and: Spastic Walking." Prairie Schooner 79, no. 4 (2005): 32-34.

“Spastic Walking” is featured in Eadweard Muybridge’s 1887 landmark publication, Animal Locomotion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements. The work is one of many included in a monumental archive of eleven volumes, 781 plates, and 19,731 photographs depicting novel perspectives in human and animal movement and anatomy. An unprecedented and financially exorbitant undertaking, Animal Locomotion was sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania alongside a cadre of influential and prominent Philadelphians, among them artist Thomas Eakins, Penn Provost William Pepper, and neurologist Francis Dercum. The publication revealed groundbreaking ways of conceptualizing time, space, and motion, while implicitly supporting tenets of social Darwinism, the now discredited theory of genetic and racial superiority. Its volumes were organized in a pseudo-evolutionary hierarchy, beginning with men engaged in athletic feats, women performing household work or posing with various objects, and children playing, followed by a cohort of disabled individuals, and ending with animals.

This photograph is plate 541 from Volume 8, a revelatory educational archive of prevalent neurological conditions in the late nineteenth century, including poliomyelitis, tabes dorsalis, lead encephalopathy, athetotic cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, congenital hydrocephalus, and others. At Dercum’s insistence, Muybridge photographed over twenty-some patients from neurology clinics at the University Hospital and Blockley Almshouse, later known as Philadelphia General Hospital. Selected patients and their nurses walked directly from the hospital to the outdoor studio through a conduit erected for this purpose.

The nude woman in “Spastic Walking” was photographed using over twenty adjacent cameras in Muybridge’s outdoor studio, which was located at the northeast corner of 36th and Pine Streets on Penn ’s campus where the Rhoads Pavilion now stands. She appears dystonic, or unintentionally postured with her head turned aside and her arm outwardly extended. As the series progress, her head turns from right to left, then right again. Hips similarly shift side to side as she staggers with an uncoordinated, ataxic gait and circumduction of the right leg. Her imbalance contrasts with the attendant to her side, who steadily guides her. Muybridge’s presentation of his subject obscures her personhood, which is eclipsed by her condition.

reflections…

Animal Locomotion solidified Muybridge’s legacy as a pioneer of cinematography at the nexus of technology, medicine, and industrial expansion. The iconicity and technical ingenuity of Animal Locomotion for its time are irrefutable; its motion studies were foundational to both twentieth-century art and medicine, influencing everything from Duchamp’s interest in temporality to Warhol’s seriality, to the work of Arthur W. Goodspeed and W.N. Jennings, who jointly developed the first x-ray image at Penn shortly after Animal Locomotion. Muybridge heralded a larger moment in which photography and imaging became essential tools for intimately examining and documenting the body for physicians and the artistic avant-garde. Strategic affiliations with scientific institutions and patronage from the intellectual elite lent further credibility to Muybridge’s reputation and his appeal to empiricism.

Yet Animal Locomotion demonstrates how scientific inquiry and cultural advancement may also mask subjective and subversive agendas advanced by those wielding financial and cultural capital. Challenging the social conventions and proprieties of the anti-vice era, the collaborators produced tens of thousands of images of nude individuals pole-vaulting, leaping, crouching, and lounging in hammocks. Muybridge purposefully sought out University athletes for their “ideal” physique, presenting them as specimens of athletic prowess. As such, the images of neurologic patients in Volume 8 assume a decidedly anthropometric, exhibitionist slant. They raise questions about the ethical representation of bodies, and the abilities of bodies that deviate from supposed norms.

How can we appreciate the collaborative and interdisciplinary ethos of projects like Animal Locomotion while also being cognizant of the sociocultural context and power dynamics that shaped its production? How can we be attentive to the ways in which sponsorship and/or institutional affiliation can normalize otherwise morally compromised endeavors? How can the arts and sciences both intentionally and unintentionally provide legitimacy for, and, at times, advance suppositions that raise profound bioethical concerns? While there is a tendency today to valorize collaborations across the arts and humanities to advance compassionate caregiving and well-being, work such as Muybridge’s reminds us that this intersectional approach has also historically dehumanized patients and human subjects. How does our attentiveness to the moral challenges that underpin Animal Locomotion allow us to be more thoughtful about medicine and arts collaborations in the present?

Contemporary writer and curator Lucy Lippard has critiqued Muybridge, particularly his lesser-known work in the American West, pre-dating Animal Locomotion. The United States government commissioned Muybridge to photograph indigenous land devoid of its inhabitants so as to naturalize colonization and further a genocidal agenda. When indigenous people were included in the photographs, the imagery was often disseminated as racist propaganda, essentializing the subject as a savage. Quoting the Hopi photographer Victor Masayesva, Lippard “sees the camera as a weapon” that can be wielded to erase, rather than to represent. She writes, “Photographers were called ‘shadow catchers’ by some tribes (the shadow referring to death, or the soul of the dead). The transfer of a black-and-white likeness to paper meant to some that a part of their lives had been taken away, to others that their vital power had been diminished.”

How does Animal Locomotion similarly employ photography for visual consumption, albeit foregrounded through technological innovation, rather than for thoughtful visibility and awareness? In other words, while images of invisibilized people, such as the patients of Blockley Almshouse, have the potential to empower their subjects, when and how does that visibility become reductive, exploitive, or dehumanizing?

sources

Brockmeier, Erica K. “A New Way of Thinking about Motion, Movement, and the Concept of Time.” Penn Today, 17 Feb. 2020, penntoday.upenn.edu/news/new-way-thinking-about-motion-movement-eadweard-muybridge.

Eadweard Muybridge: Animal Locomotion: Huxley-Parlour Gallery.” Huxley Parlour, huxleyparlour.com/exhibitions/eadweard-muybridge/.

Gordon, Sarah. Indecent Exposures: Eadward Muybridge’s “Animal Locomotion” Nudes, 2015. Yale University Press.

Lanska, Douglas L. “The Dercum-Muybridge collaboration for sequential photography of neurologic disorders.” Neurology Oct 2013, 81 (17) 1550-1554; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a95894.

Malamud, Randy. "Eadweard Muybridge, Thief of Animal Souls." The Chronicle of Higher Education 56, no. 39 (2010). Gale In Context: Biography (accessed January 18, 2021).

Manjila, Sunil et al. "Understanding Edward Muybridge: historical review of behavioral alterations after a 19th-century head injury and their multifactorial influence on human life and culture". Neurosurgical Focus FOC 39.1 (2015): E4. < https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.4.FOCUS15121>.

“Muybridge's Animal Locomotion Study.” University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania, archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/muybridge.

Radiology: Penn Medicine: Department History. Penn Medicine, www.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/department-of-radiology/about-penn-radiology/department-history#tab-12.