Rx 15 / Rachel Weeping

Draw not the curtain, if a tear

Just trembling in a parent's eye

Can fill your gentle soul with fear

Or arouse your tender heart to sigh

A child lies dead before your eyes

And seems no more than molded clay

While the affected mother cries

And constant mourns from day to day—Charles Wilson Peale, painting inscription (1782)

Mrs. Peale Lamenting the Death of Her Child was originally a posthumous solo portrait of artist Charles Willson Peale’s (1741–1827) recently deceased daughter, Margaret. A victim of smallpox and the fourth deceased Peale child, Margaret lies ready for burial, her sepulcher-like complexion absent disease. Her mouth is held closed by the strap anchored under her chin, arms softly bound together by a ribbon. The white garments and bed linens evoke spiritual purity and rebirth.

Mrs. Rachel Peale, who later died during the birth of their tenth child, was added into the composition four years after its initial completion. Her strong verticality contrasts with the horizontality of the child. Christian iconography of Madonna and Child is intentional, embodying the sanctity of this familial bond in a final moment of mourning. Peale uses a somber palette of muted, desaturated colors and concentrates light and shadow to emphasize specific areas of the composition for dramatic effect. The woman’s dark hair frames her face and is set against the shadowed background, illuminating her visage in full, cool light. A pool of light gathers in the lower right corner and silhouettes the medical bottles on the table.

In Peale’s day, it was common for a child to live and die without visual recording. Pre-dating photography, posthumous portraiture thus preserved a unique identity in the bosom of family life, and became a vibrant genre of American painting in its own right. Deceased children were often portrayed as enlivened and animated, partaking in pleasurable pastimes to conjure pleasant memories for the family in the private home. That is, the portraits conveyed some semblance of who the child was in life. Here, we have no such insight—Margaret’s corpse lies before us divested of identity, her anonymity a foregone conclusion.

REFLECTIONS…

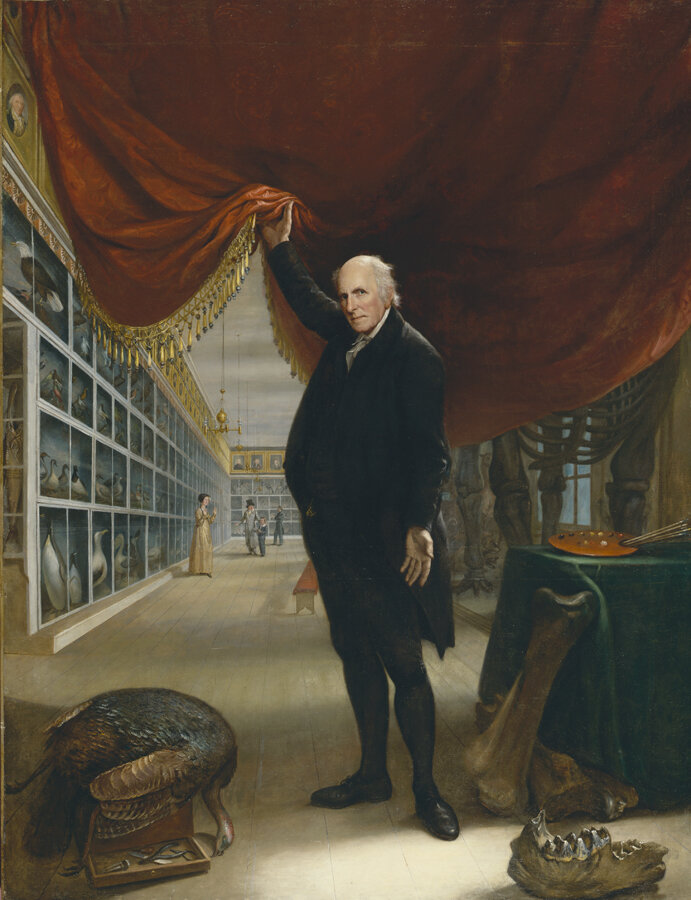

A quintessential showman, Peale dramatically displayed Mrs. Peale behind a dark curtain in his museum of curiosities, The Peale Museum, one of the first museums in America. Alongside taxidermy and portraits of founding fathers and accompanied by an inscription penned by Peale to warn viewers of its sensitive nature, Mrs. Peale is an exploitive rendering of childhood death. We are left to ponder the intent of this painting and consider whether it was created for private mourning or public exhibition and entertainment, or both, at varying stages of completion.

How do Peale’s intentional gallery theatrics convey a shocking, even perverse, exhibit of a dead child, likening this scene to that of a pile of mastodon bones, also exhibited at this museum? Conversely, does Peale succeed in tenderly memorializing the brief life of his young daughter? Next, consider the weeping Mrs. Peale, irises upturned in lamentation with pearlescent droplet tears redolent of Le Brun’s tristesse . How does Peale fetishize bereavement in this painting?

Do sensationalized or contrived plays on the drama of suffering and mourning offer a form of consolation, or do they simply further the appeal and spectacle of tragedy and melodrama? As medical professionals, how do we witness or partake in similar paradigms of grief within the clinical setting? How can we reconcile the pain of intimate loss with ornate renderings of anguish?

How does Mrs. Peale embody the enterprising nature of grief as a commodity or exhortation for charity? How might the painting represent a precursor of sorts to the visual rhetoric utilized by children’s hospitals, non-profit foundations, and crowdfunding campaigns for various gains? Consider the prominent whiteness of the emblematic mother-child dyad in Mrs. Peale and in many contemporary, commercialized images of ill or dying children. Does this prompt us to reconsider ‘worthy’ images of grief? In other words, how do we determine the images we care about and perhaps more importantly, the ones we don’t? How does this speak to the significance of visual representation as it pertains to inequity, systemic racism, and social determinants of health in pediatric disease and death?

Special thanks to Bryanna Moore, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine.

sources

Kennedy, Randy. O Death: Posthumous Portraits at the Folk Art Museum. The New York Times, 28 Sept. 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/10/02/arts/design/o-death-posthumous-portraits-at-the-folk-art-museum.html?_r=0.

Lloyd, Phoebe. "A Death in the Family." Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 78, no. 335 (1982): 3-13. doi:10.2307/3795306.

Marks, Arthur S. "Private and Public in the Peale Family: Charles Willson Peale as Pater and Painter." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 156, no. 2, 2012, pp. 109-187.

McHugh, Brendan, and Ani Kodjabasheva. “Securing the Shadow: The Folk Art Museum Chronicles Death in Early America.” Brut Force, 10 Jan. 2017, brutforce.com/securing-the-shadow-folk-art-museum/.

Peale, Charles Willson. Mrs. Peale Lamenting the Death of Her Child. 1772. Philadelphia Museum of Art, philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/71982.html?mulR=755986862%7C6.

“Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America.” Exhibitions, American Folk Art Museum, 2016, folkartmuseum.org/exhibitions/securing-the-shadow-posthumous-portraiture-in-america/.