Rx 29 / Still Life

Cézanne’s are records of the experience of continuous movement through space in time. Cézanne’s paintings “change without ceasing” and the painter himself was the first modern artist to create an image of time.

- George Heard HamiltoN

Paul Cézanne’s (1839-1906) Still Life With Skull was completed two years before the turn of the century, a period that would mark a significant shift in the artist’s personal life and in the trajectory of twentieth-century painting. In Cézanne’s last years, he suffered from strained relationships with family and lived alone in Aix-en-Provence where he hermetically pursued studies of color and depth in still life series and landscapes. The resultant paintings break down static scenes into dynamic geometric forms with bold, directional brushstrokes and juxtaposed colors that form spatial planes.

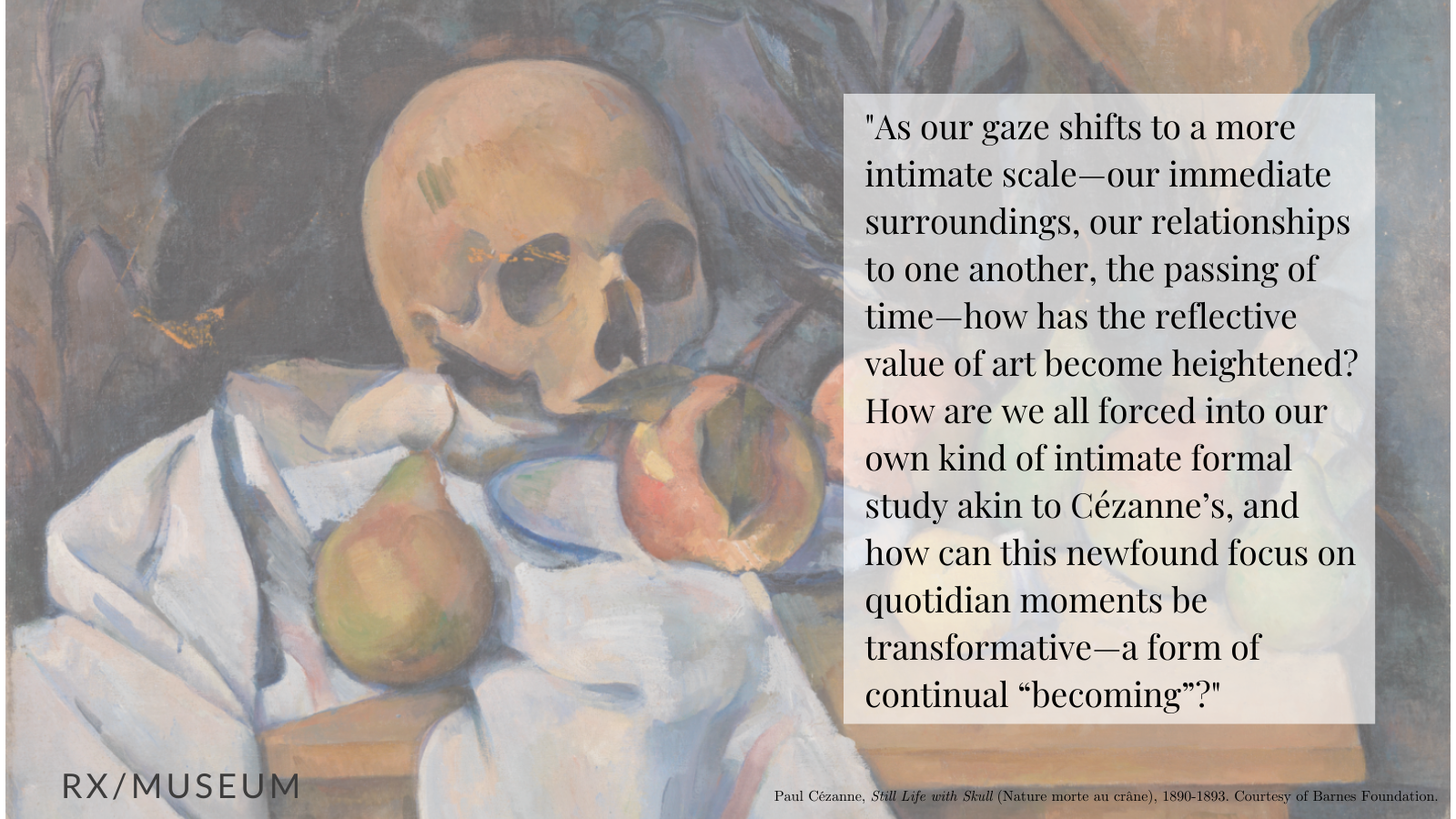

Still Life with Skull is an example of his ability to portray familiar objects in unexpected and animated ways, striking a balance between abstraction and illustration. Here, a human skull sits atop a loosely folded piece of drapery. The curvature of the skull echoes the strewn fruit, its scale differentiating it from the other forms. The peach on the tilted plate or the pear set at the edge of the table convey tension and precarity. Cézanne provides a slightly distorted view of the table on which the skull and fruit rest. On the left, the table is directly in front of the viewer whereas on the right, the view is one from slightly above. The drapery separates the disjunction between these two planes.

The classic memento mori tableau of rotting fruit and a human skull reveals disruption in its details. A bright line of orange paint runs across the eye socket and the wall paper depicted behind the skull—likely the result of the artist stacking up paintings in his studio before they were completely dry. Cézanne opted not to remove the orange paint before sending the work to Ambroise Vollard’s gallery for sale. At the painting’s right edge, the white of the canvas emerges from an abandoned blue colorfield. The exaggerated dark outlines of the fruits reveal that the artist never sought to reproduce static reality, as many of his predecessors had.

Cézanne recognized that painting, in its flatness, was inadequate to mimic the depth and contours of space. In intentionally exposing the limits of the medium, he, like other Modernist painters, broke conventional rules of perspective to fully embrace the challenge of representing lived experience. Widely thought to have occasioned the turn to abstraction, Cézanne’s late works, including Still Life with Skull, innovated new modes of representation and, in turn, new ways of seeing.

reflections…

Historians have remarked on the resounding consonance between Cézanne’s work and that of French philosopher Henri Bergson, who released his landmark Creative Evolution (1907) the year following Cézanne’s death. Bergson posited that each living moment is not finite or fixed, rather the culmination of all that has happened before and the anticipation of all that will happen next—a perspective that Cézanne conveyed in his late work. As art historian George Heard Hamilton wrote, Cézanne’s work is the “pictorial equivalent of the Bergsonian concept of space as known only in and through time.”

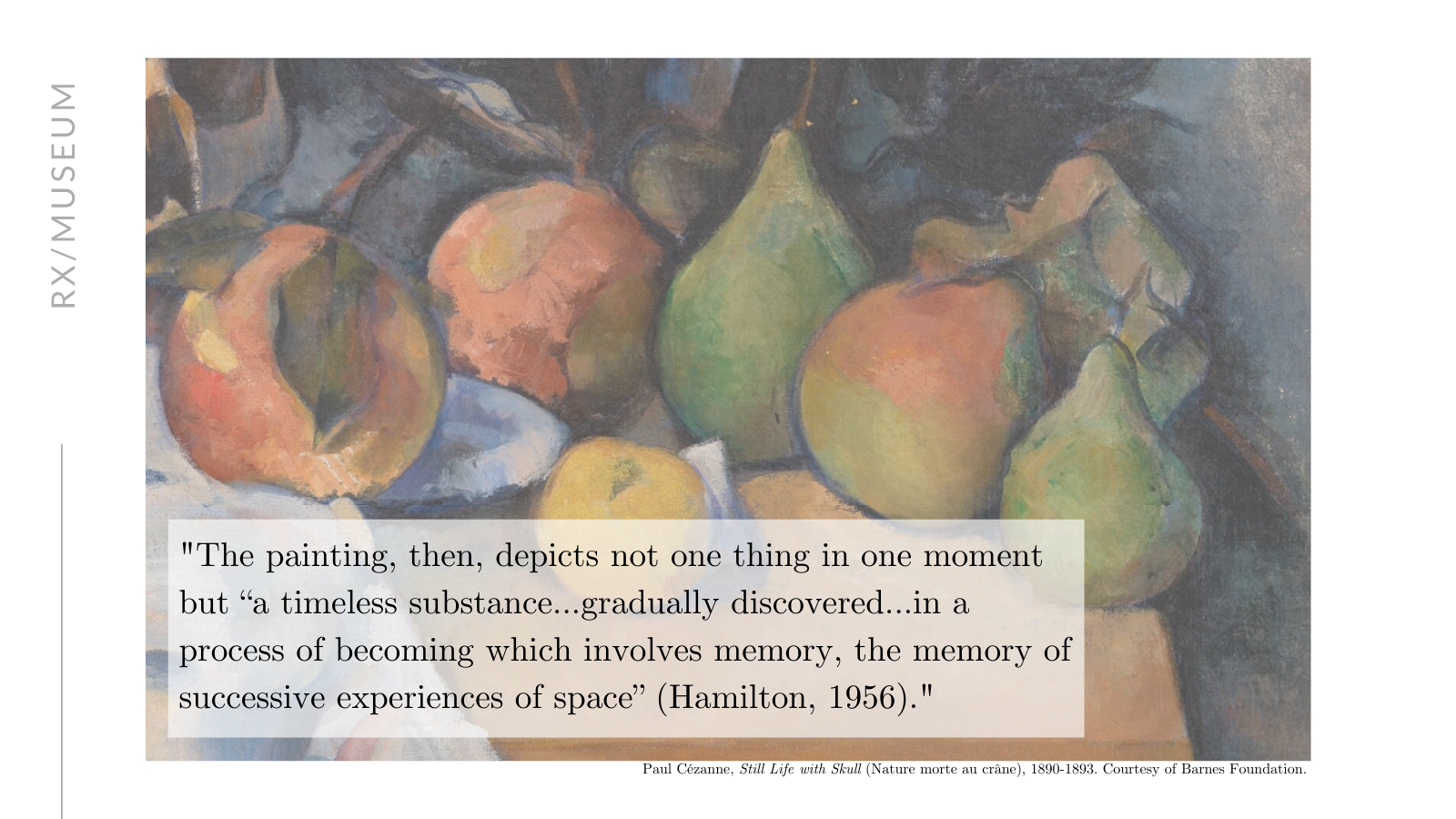

We are reminded of the fruit in varying stages of ripeness in Still Life With Skull. The spoiled fruit in the center caves in, contrasting dramatically with the unblemished pears flanking the table. The painting, then, depicts not one thing in one moment but “a timeless substance...gradually discovered...in a process of becoming which involves memory, the memory of successive experiences of space.”

With an eye towards Bergson’s work, how might we recognize the dimensions of grief, particularly for frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic who have continually endured and witnessed extraordinary pain and suffering? Though each moment is not marked by loss, trauma, or illness, our collective reality continues to be defined by all that came before and all that will come after. How can clinicians be attentive to a similar dynamic at play for patients as their life experiences come to bear on a momentary medical encounter? How can we better acknowledge individual struggles in our communication and empathy with one another? Just as Cézanne and Bergson were committed to the study of duration, how can we create space for self-care and grace amidst this pandemic and beyond?

Many of Cézanne’s works have an apparently unfinished quality; he was known to intentionally leave parts of the canvas unpainted. Heard Hamilton wrote, “There could be no ‘finished’ signed and dated masterpieces in this process which being in itself incomplete prohibited the artist from ceasing at any given point.” A recent article by Hisham Matar in The New York Times Magazine similarly asserts a painting, in its “becoming,” is never finished, “that it must continue to do its work long after it has been hung on the gallery wall, that a picture relies on us to complete it.”

In this way, a Cézanne still life is, in fact, a dynamic encounter. It is incumbent on the viewer to actively engage with the work, and to see it as a constellation of experiences, perspectives, and memories. Matar goes on to describe the dynamism and dialogue of artworks with the unfolding of history, questioning what happens—to art and to us—when art is not seen, particularly in times of upheaval and uncertainty. He argues a painting is incomplete without its viewer, so too a society and a culture are without art.

As our gaze shifts to a more intimate scale and we consider our immediate surroundings, our relationships to one another, the passing of time, how has the reflective value of art become heightened? How are we all forced into our own kind of intimate formal study akin to Cézanne’s, and how can this newfound focus on quotidian moments be transformative, a form of continual “becoming”?

sources

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution, 1944. Modern Library.

Heard Hamilton, George. “Cezanne, Bergson, and the Image of Time.” College Art Journal 16: 1 (Autumn, 1956): 2-12.

Matar, Hisham. “Visiting the Museum in My Mind.” The New York Times. The New York Times, May 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/magazine/covid-quarantine-williruge.html.

Snyder, Michael. “Still Life With Fly Swatter, or Hourglass, or Lemons.” The New York Times. The New York Times, May 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/12/t-magazine/photographers-coronavirus-still-life-pictures.html.