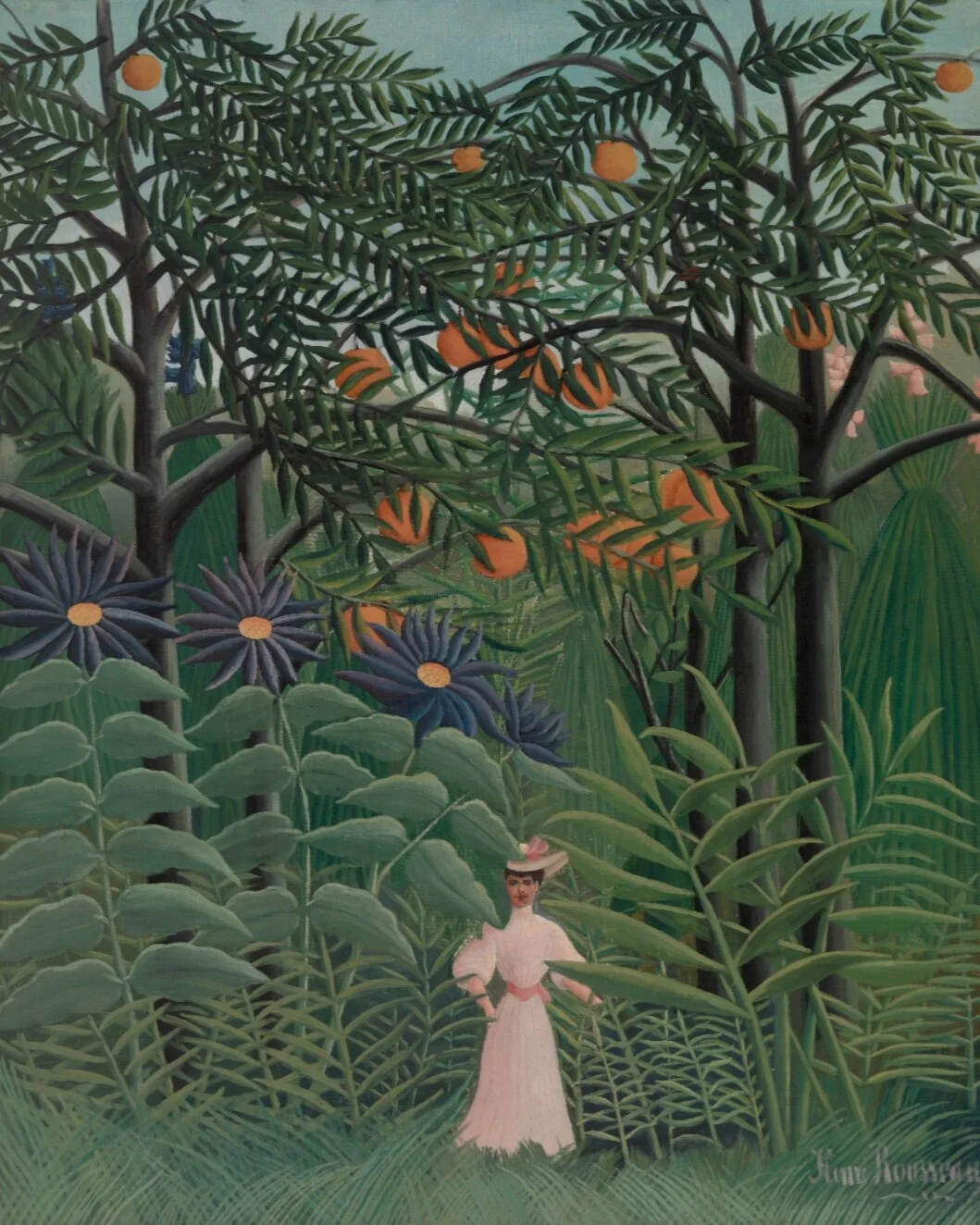

Rx 11 / The Exotic Forest

A woman mysteriously emerges from the wall of dense green vegetation. She inexplicably appears into the clearing as a visual focal point, dwarfed and partially hidden by larger-than-life flora. Her modified hourglass figure is echoed in the tall gathered verdure within the deeper landscape. Repetitively aligned foliage creates rhythmic patterns with symmetrical clusters of grasses, splayed leaves and fronds, and radiating flower petals. Oranges set within the canopy of trees add syncopated variety to the scene. The elegant attire and formal posture of the woman is in tension with the verdant landscape to an almost absurd degree, as if her Parisian stroll has suddenly brought her into direct proximity with the French colonies. An eerie sense of calm and unnatural stillness lingers, suspending the woman and viewer in an incongruous, lush, colonial reverie.

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) painted twenty-six variations of his iconographic jungle vistas, each a distinct, dramatic narrative rendered in a kaleidoscope of enchantment. Rousseau was not concerned with botanical accuracy or scientific acumen. Rather, he sought to portray a novel pictorial experience solely for viewing pleasure. While he never traveled internationally, his compositions were inspired by visits to the Jardins des Plantes in Paris, the cinema, zoological exhibits of taxidermy, and world fairs, and reflected the popular desire for the byproducts of colonialism in his time. The distant, mysterious lands he portrayed were fantasized, and feared, conveniently depopulated of indigenous peoples; perhaps Rousseau’s jungle motifs are an allegory of Paris and its anxieties of the other and the unknown, or a reflection of his own desires to escape the confines of urban life. As one critic wrote, “[Rousseau’s forest] is the virgin forest with its terrors and its beauties, that we dream of as children…the virgin forest as a creation of fantasy.”

Reflections…

In Rousseau’s romantic vision of a French colony, the violence of colonialism has been erased in favor of an uninhabited landscape. How do Rousseau’s jungle vistas resemble an exotic botanical garden of sorts and convey an expression of imperial power? How have such works contributed to a slanted narrative of colonialism that is divorced from its genocidal realities? How can formal medical education today better acknowledge the legacy of colonialism in the history of medicine—specifically, the ways in which medicine has been wielded against colonized communities?

Rousseau is regarded as the ultimate naïve artist. Despite poverty, older age, anonymity, and no formal training, his intuitive skill and blatant ambition propelled him into the upper echelons of the avant-garde art world. He forged his own version of success when hierarchical social and academic connections dictated artistic merit. Critics initially derided Rousseau’s art as “naïve,” a term connoting lack of traditional expertise. And yet, because of this, Rousseau’s compositions were immediately noteworthy at the Salon for their powerful imaginative perspective and striking color palette. His highly individualistic style and disregard for convention paved the way for modern, progressive artists.

In contrast, medicine strives to be evidence based. We in fact don't want an ethos of individualism where care is guided by feeling, intuition and idiosyncratic proclivities. This emphasis, however, on conformity and standardization may inflict significant cognitive and emotional dissonance for resident physicians (Wyatt, 2018). One study demonstrated that trainees feel they are being trained as robots, divested of humanistic qualities and parts of their identity in favor of developing a new all-consuming professional identity (Wyatt, 2018). This erosion of individual identity may result in a loss of cultural capital and diversity that training programs initially seek in applicants.

How can programs and institutions better integrate support of cultural, ethnic, and experiential resident diversity throughout training? How can they reimagine a more thoughtful and inclusive approach that respects difference even as it cultivates adherence to shared biomedical principles and values integral to the rigorous corpus of medical training? How might humanistic-centered curricula and critical reflection contribute to this dialogue?

SOURCES

“Henri Rousseau. The Dream.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/79277?sov_referrer=artist&artist_id=5056&page=1.

Hester, Jessica Leigh. “The Misery of a Doctor’s First Days.” The Atlantic, 1 Oct. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/the-misery-of-a-doctors-first-days/408004/.

Phelan, Joseph. "Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris." New Criterion, vol. 25, no. 1, Sept. 2006, p. 98+

Rousseau, Henri, Henri Rousseau : Essays. New York, Museum Of Modern Art; Boston, 1985.

Wyatt, T.R., Egan, S.C. & Phillips, C. “The Resources We Bring: The Cultural Assets of Diverse Medical Students.” J Med Humanit, vol 39, 503–514, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-018-9527-z