Rx 12 / Strange Fruit

here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

for the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

for the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

here is a strange and bitter crop.- abel meeropol, “Strange fruit”

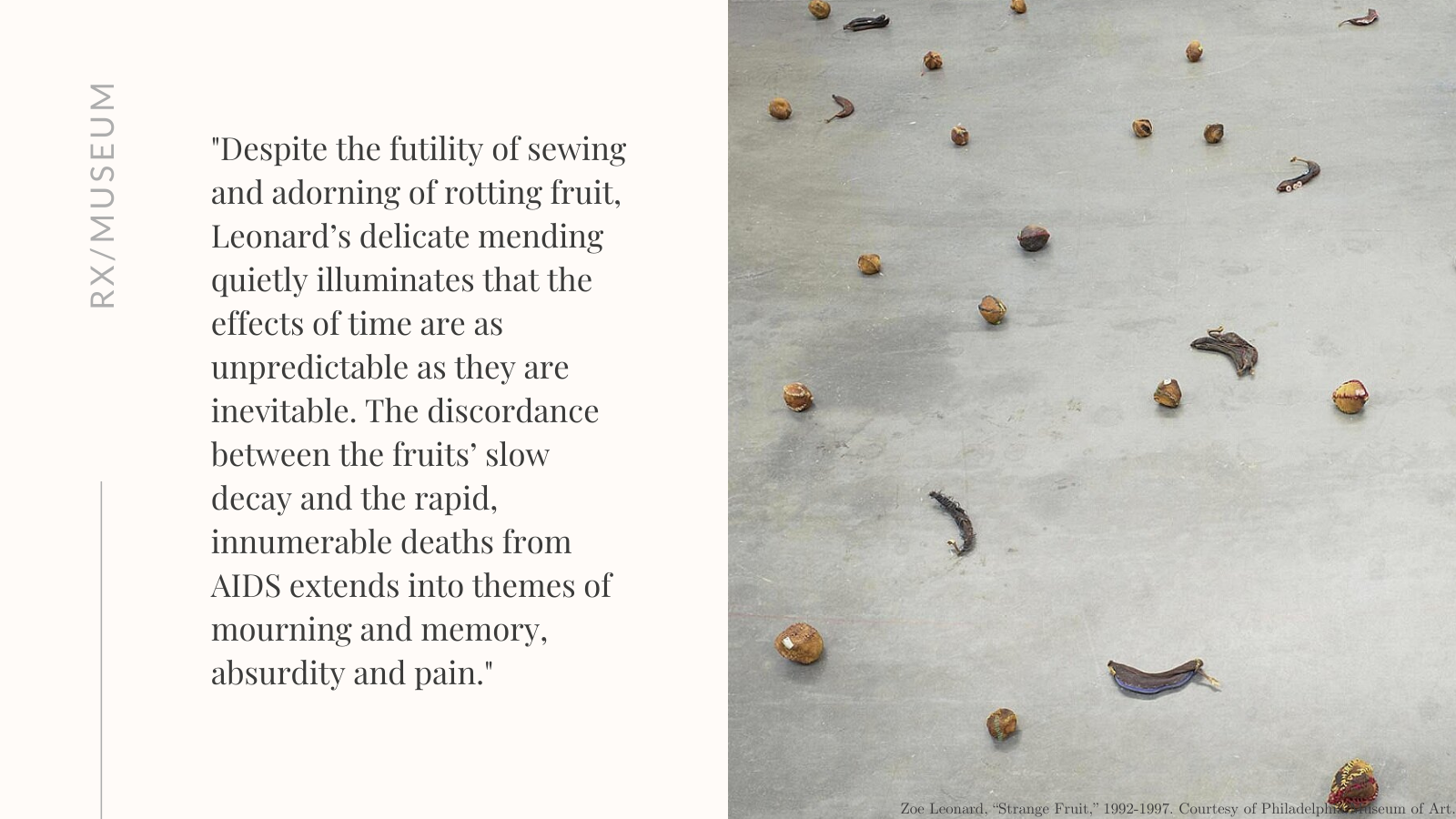

Strange Fruit was exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1998. Artist Zoe Leonard (b. 1961) began to assemble the installation shortly after the death of fellow artist David Wojnarowicz as a means of personal consolation amid the AIDS crisis. A prominent AIDS advocate and supporter of queer liberation in the 1980s and 1990s, Leonard’s multimedia work explores mortality and displacement within the urban landscape. Invoking the 1937 Abel Meeropol anti-racist protest song popularized by Billie Holiday and Nina Simone, Strange Fruit is unique in composition, thematic focus, and a personal politics of justice for the marginalized. A friend of Leonard’s explained: “When Zoe started making this work, our friends were dying — daily, weekly, relentlessly. Wasting in front of our eyes.”

Strange Fruit is at once a meditation on loss and a testament to needless suffering from government complacency. Leonard purposefully abstained from a preservation technique, contesting the notion that art should be maintained. The fruit skins—emptied, dried, faded, repaired, ornamented—have the feel of photographs or religious reliquaries. Despite the futility of sewing and adorning of rotting fruit, Leonard’s delicate mending quietly illuminates that the effects of time are as unpredictable as they are inevitable. The discordance between the fruits’ slow decay and the rapid, innumerable deaths from AIDS extends into themes of mourning and memory, absurdity and pain. As described by then Philadelphia Museum of Art curator Ann Temkin, “Maybe this is not a universe without wounds, reconstructions, scars, or death. Sometimes we are ready to know there can be beauty in cracks and in loss.”

reflections…

Zoe Leonard and decaying fruit. Jerome Caja and human ashes. Barton Lidice Beneš and red ribbon. Felix Gonzalez-Torres and empty pillows. How do these artistic renderings of the body force us to acknowledge the role of societal homophobia and government indifference in exacerbating the AIDS epidemic and resultant preventable deaths? Similarly, how do such pieces give voice to communities most devastated by HIV and the deeply entwined, intergenerational struggles of poverty, racism, and sexism?

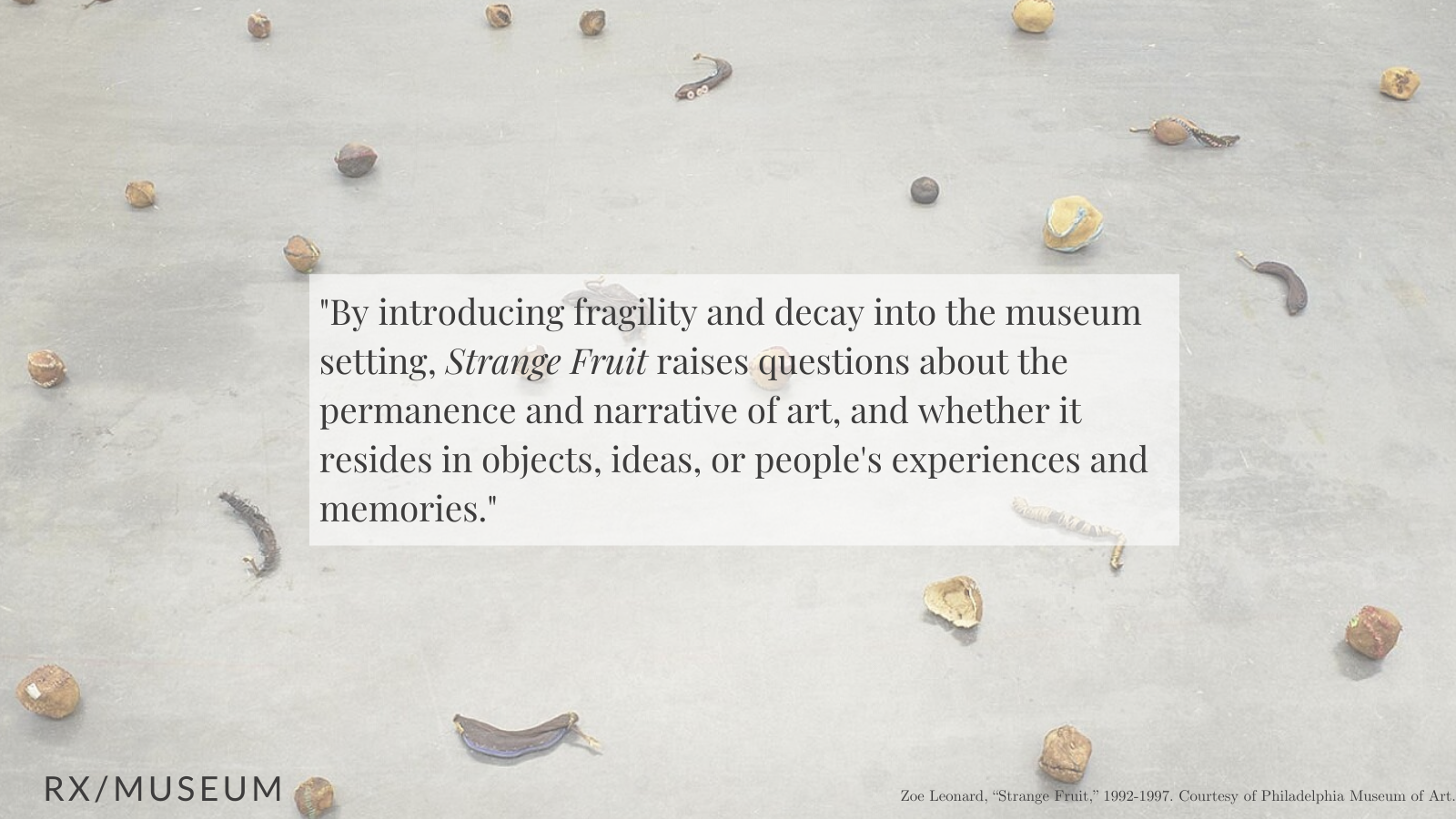

Preserving impermanent works is a fundamental practical challenge for museums. Although they are institutions intended to care for static objects, they are often unaccustomed to archiving organic, disintegrating works. By introducing fragility and decay into the museum setting, Strange Fruit raises questions about the permanence and narrative of art, and whether it resides in objects, ideas, or people's experiences and memories.

We might say that these challenges similarly implicate the clinical setting. While museums are often predicated on memorializing the past, hospitals are institutions of transience. Yet both share in the ongoing repercussions of traumas, pain, and struggles of their communities and society. To what extent can such institutions founded on colonialism, racism, sexism and other forms of inequality and oppression, strive for objectivity in their narratives or conversely, commemorate and give voice to quietly extinguished lives and lay bare the systemic injustices at fault?

“In June of 1983, at the Fifth Annual Gay and Lesbian Health Conference in Denver, Colorado, a group of about a dozen gay men with AIDS from around the U.S. gathered to share their experiences combating stigma and advocating on behalf of people with AIDS [...] They wrote out a manifesto, now known as “The Denver Principles,” outlining a series of rights and responsibilities for healthcare professionals, people with AIDS, and all who were concerned about the epidemic. This was the first time in the history of humanity that people who shared a disease organized to assert their right to a political voice in the decision-making that would so profoundly affect their lives.

The first statement reads: “We condemn attempts to label us as "victims," a term which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally "patients," a term which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are "People With AIDS."”

How does the medical establishment perpetuate the narrative of patient as victim, and is this problematic? How does stigma from society and/or clinicians continue to oppress patients suffering from certain value-laden illnesses? How can clinicians create space and afford greater dignity for patients to similarly advocate for themselves, in community and solidarity?

Sources

Hallstead, Kate. “A Body of Work: Corporeal Materials, Presence, and Memory in Jerome Caja’s Exhibition, Remains of the Day.” ONCURATING, https://www.on-curating.org/issue-42-reader/a-body-of-work-corporeal-materials-presence-and-memory-in-jerome-cajas-exhibition-remains-of-the-day.html#.XyibzShKh3h.

Henrich TJ, Lelièvre JD. Progress towards obtaining an HIV cure: slow but sure. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(5):381-382. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000492

Kerr, Theodore. “The Denver Principles.” ONCURATING, www.on-curating.org/issue-42-reader/the-denver-principles.html#.XyidryhKh3i.

Traps, Yevgeniya. “Zoe Leonard: Archivist of Feeling.” The Paris Review, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/03/16/zoe-leonard-archivist-of-feeling/

Whitney Museum of American Art. (2018, March 24). Zoe Leonard: Strange Fruit [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sfD8iWicHB4&feature=emb_err_watch_on_yt.

“Zoe Leonard.” Artists - Zoe Leonard - Hauser & Wirth, www.hauserwirth.com/artists/2847-zoe-leonard.

“Zoe Leonard.” Guggenheim Collection Online, 23 May 2013, www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/zoe-leonard.