Rx 23 / The Riffian

And the Riffian! How splendid is he, this great devil of a Riffian, with his angular face and his ferocious build! How can you look at this splendid barbarian without thinking of the warriors of days gone by?

- Marcel sembat, 1913

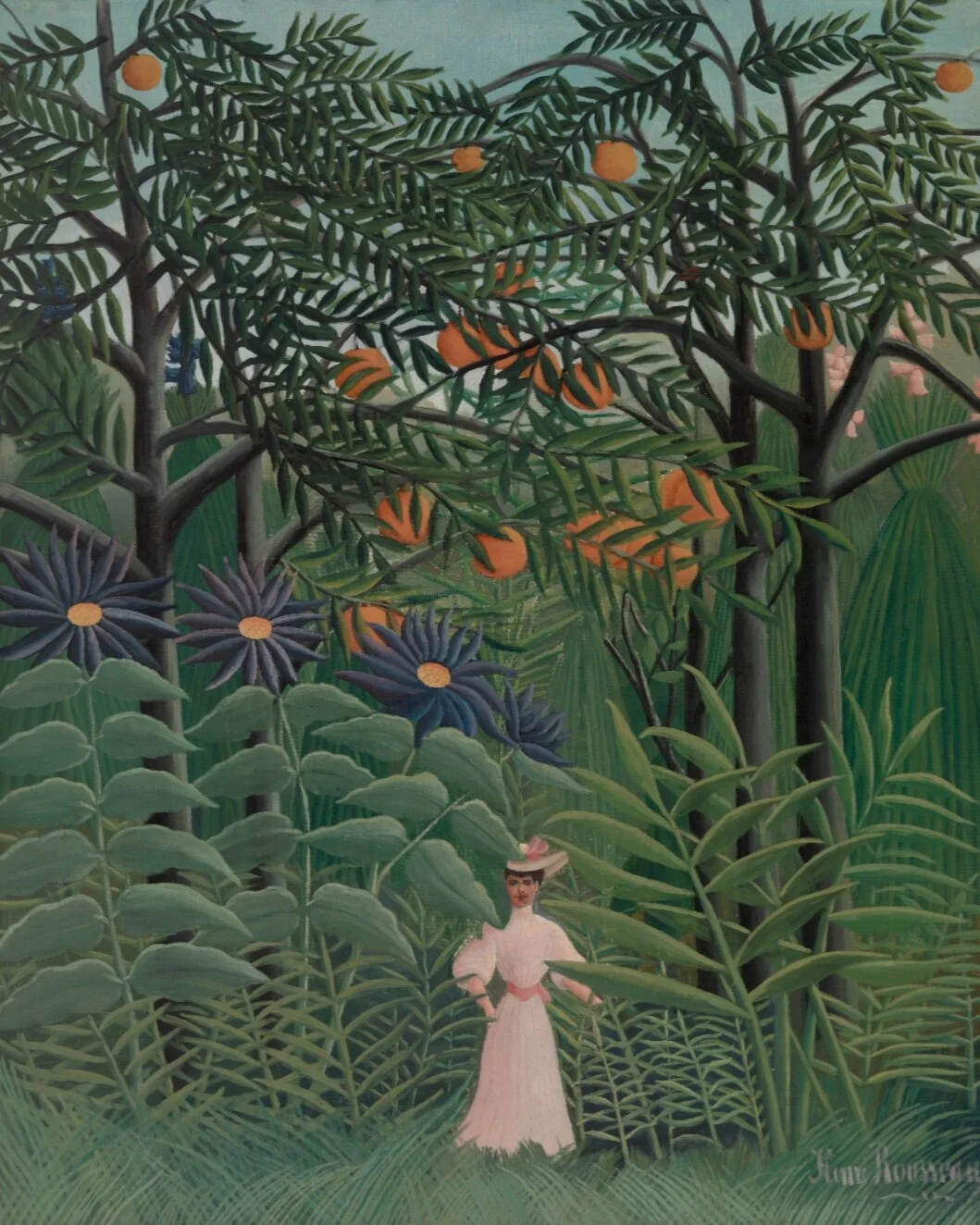

Seated Riffian is one of two paintings by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) portraying young men from the Rif mountains of the Kabylia region in Northern Morocco. Matisse completed Seated Riffian while visiting Tangier in 1912—a year marked by political upheaval as France undertook colonization of Morocco. It is significant, then, that Matisse, a Frenchman, chose to paint this particular sitter.

Although Matisse was generally disinterested in sociocultural and political matters, focusing more on formal and aesthetic concerns, the painter’s attitude towards his subject is perhaps suggested by a color postcard he sent to his son Jean on January 10, 1913. The note reads, “I am sending you a chap from the village of Raisuli [sic], a well-known bandit, who robbed travelers in the Tangier region some years ago. To quiet him down the Sultan gave him a province to govern. In that way he has become an official thief who bleeds those under him.”

The sitter, represented on the postcard and in the painting, is characterized primarily by his resplendent costume. In this way and others, the work typifies Orientalism, a term famously coined by the late cultural critic Edward Said to describe the central role that the ‘East,’ both imagined and real, played in the development of Western society. Said wrote in particular about the tendency of Western artists to represent the ‘East’ as mystic and its people as debaucherous, pointing to the dually romanticized and materially violent nature of the relationship of the West to the East. These power dynamics are implicitly painted into Seated Riffian, with Matisse determining how this unnamed other will be represented and, in turn, perceived. As much as Matisse tried to distance himself from a troubling historical reality with a tendency towards Modernist abstraction, Seated Riffian does not fully evade a political reading. As art historian Roger Benjamin writes, “For Matisse, the authenticity of representation depended on what the artist sees and how plausibly his imagination transforms it rather than on any ‘reality’ of documentary observation.”

reflections…

Much of the painting’s expressive power results from its complex engagement with the Orientalist tradition of portraiture. Matisse was, above all, concerned with aesthetic questions, particularly the confrontation of his own formalism with the Orientalist tradition in Western art. His presentation of the Riffian, and the importance given to the man’s costume, suggest that he did not fully escape a cliché of the Orientalist gaze: the half-length depiction of a ferocious Arab warrior in traditional regional dress.

How does the way in which medical providers perceive patients compare to Matisse’s interpretation of his subject in Seated Riffian? In medicine, do we rely on and prioritize distanced, cursory viewing rather than thoughtful engagement? How can we create relationships that are less essentializing?

In contrast to Orientalism’s reliance on imagining the ‘other,’ the study and practice of medicine depends on objective, evidence-based scientific reasoning. Yet, the delivery of healthcare and the clinical encounter are embedded with subjective interpretation, bias, and socioeconomically and culturally-determined notions of race. Physicians are often tasked with providing medical recommendations and treatment strategies weighted heavily by racial optics. Social constructs, as opposed to innate, genetically determined risk factors, are frequently operationalized in a biomedical context, potentially driving patient outcomes and racialized health disparities. How can those in medical education, research, and clinical care recognize—as Matisse and other European artists in colonial Northern Africa were perhaps unable to—that their fields are inherently entwined with complex social and political contexts?

This thwarted “authenticity of representation”—of race as a biomedical entity—is pervasive in pre-clinical medical education and extends into clinical training and practice. A 2016 Academic Medicine article summarizes: “The inaccurate portrayal of race in medical education as biologic reifies its legitimacy as a biomedical variable despite the imprecisions of this premise. This may cause physicians to employ racial signifiers as clinically meaningful without full examination or understanding of their complex formation.” Medical students are taught to associate specific medical conditions with race, effectively pathologizing race to a White standard. The article also notes that medical school lectures and standardized licensing exams are fraught with diagnostic ‘hints’ in which race functions as an illness signifier. The authors further contend that “using race without social contextualization may serve to strengthen existing stereotypes and misconceptions of genetic immutability.”

How do we critically examine and evaluate the representation of race in undergraduate medical education and beyond? How do we implement structural change at an institutional and cultural level and ultimately work to address racial disparity in medical curriculum? How do we underscore the necessity of racially-informed medical education and recognize how racial signifiers in the clinical encounter can, like Orientalist tendencies in modern art, be reductive?

sources

“About Seated Riffian.” Art Speaks, Philadelphia Museum of Art, www.philamuseum.org/booklets/9_56_118_1.html?page=3.

Benjamin, Roger. "7. Matisse and Modernist Orientalism". Orientalist Aesthetics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019.

Cowart, Jack. Matisse in Morocco: Paintings and Drawings,1912-13. Thames & H., 1992.

Darwent, Charles. “Visual Art: The Moor in Matisse.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 22 Oct. 2011, www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/visual-art-the-moor-in-matisse-1129359.html.

Kimmelman, Michael. “How the Spirit Of Morocco Seized Matisse.” Art View, The New York Times, 18 Mar. 1990, www.nytimes.com/1990/03/18/arts/art-view-how-the-spirit-of-morocco-seized-matisse.html.

Miller, Luree. “In Search of Matisse's Morocco.” The Washington Post, 11 Mar. 1990, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/travel/1990/03/11/in-search-of-matisses-morocco/7cfeda0d-2bb4-4b02-bba0-ece643583fa9/.

Tsai, Jennifer. “What Role Should Race Play in Medicine?” Scientific American, 12 Sept 2018. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/what-role-should-race-play-in-medicine/.

Tsai J, Ucik L, Baldwin N, Hasslinger C, George P. “Race Matters? Examining and Rethinking Race Portrayal in Preclinical Medical Education.” Acad Med. 2016 Jul;91(7):916-20. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001232. PMID: 27166865.