Rx 32 / Water Urn

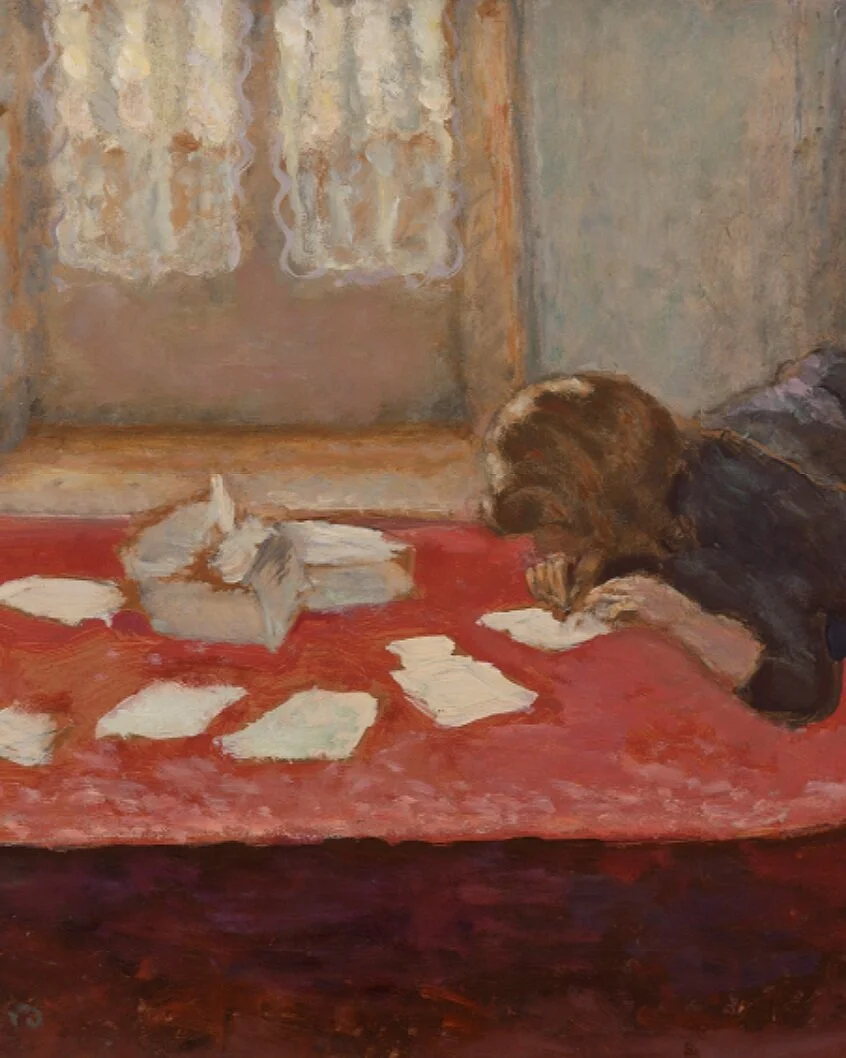

We have learned from Chardin that a pear is as living as a woman, that an ordinary piece of pottery is as beautiful as a precious stone.

- Marcel Proust

In a cool, dark basement room, a woman fills an earthenware jug with water from a large copper urn. We see an array of buckets and pans, some firewood, a leaning broomstick, a hanging rack of sinewy, fatty meat. This domestic scene provides a glimpse into the daily “below stairs” life in a wealthy eighteenth-century French household. Note the range of textural elements—the hanging meat casting a shadow on the urn; the reflective vase; the fabric of the subject’s dress gathering

as it hangs. Painter Jean-Siméon Chardin was particularly well known for his handling of white paint, mainly concentrated here in the subject’s bonnet and jacket. The white paint contrasts with an otherwise dark brown palette, and is set off against cool colors like the blue apron and her red and blue striped skirt. The painting’s granular texture evokes starched and coarsely woven cloth; the dense application of paint with a loaded brush conveys a sense of the artist’s labor, which mirrors its depiction of the subject’s labor.

In the background, an open wooden door reveals another woman sweeping next to a small child. Doorkijkje, or view through a doorway, is a classic Dutch technique, deftly utilized here to demonstrate both artistic mastery and to honor the communal effort and production-line nature of everyday tasks. Perhaps the most profound gesture of this work resides in the contrast between the two rooms depicted. The dark, below-ground work room gives way to a clean, light living space just a few steps above. As the broom leaning against the urn tilts rightward, its counterpart emerges in the hands of the woman sweeping in the background, creating continuity between the otherwise distinct spaces.

Chardin’s oeuvre emphasized la vie silencieuse, or the silent life. His nuanced light and dark palettes emanate a visually dignified richness to other- wise rote motifs of domesticity. In many ways, his artistic practice mirrored the labor of his subjects; he worked slowly and methodically on a painting over many years, producing only about four works annually. His fascination with genre scenes contrasted with the large-scale history paintings that were a staple of the annual Salon exhibitions and prized by the French academic painters. At a mere fifteen by seventeen inches, the diminutive Woman Drawing Water from a Water Urn is often paired with another Chardin of similar proportions, The Washerwoman. The two hang alongside one another in Room 3 at the Barnes Foundation.

reflections…

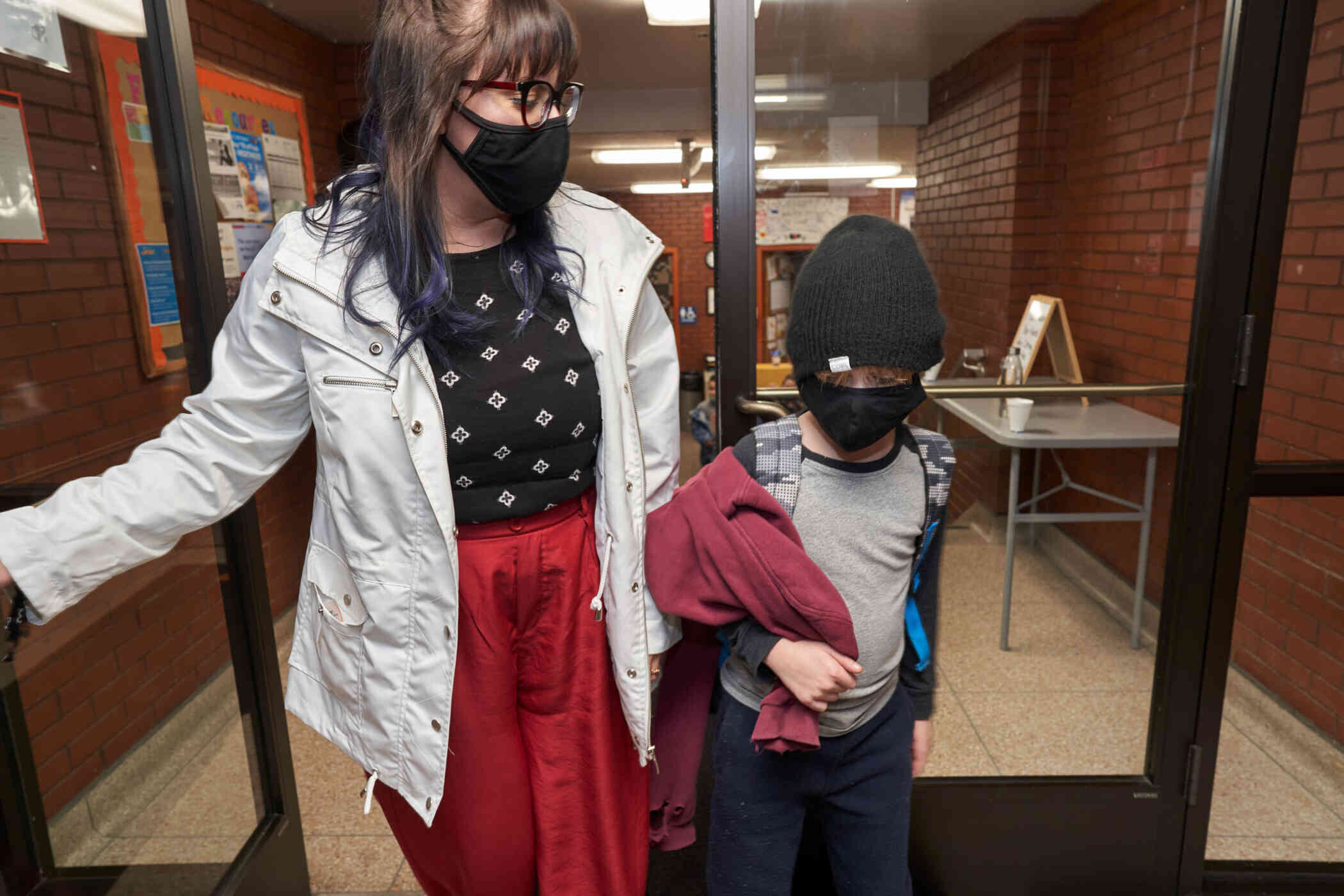

Chardin’s portrayal of the home can be understood as a microcosm of eighteenth-century culture and moral values, and in particular, a woman’s place within this realm. For some, The Water Urn might call to mind the outsized and unacknowl- edged role that women—particularly mothers, working women, and women of color—continue to play in the United States today. Consider the following portraits of working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic by Brenda Ann Kenneally, published in The New York Times under the title Three American Mothers, On the Brink. The series similarly, if inadvertently, utilizes doorkijkje to provide glimpses into private domestic life—a contemporary commentary on la vie silencieuse.

How do these intimate representations of the home cast light on dynamics in the professional realm, such as the unacceptably high attrition rate for women in academic medicine? A 2014 Association of American Medical Colleges study, for example, found that women have made up about half of all medical school graduates. But they account for only nineteen percent of medical school full professors and eleven percent of medical school deans. An October 2020 study demonstrated a proportional deficit of manuscripts submitted by younger cohorts of women academics during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although Chardin’s is an idyllic, romanticized portrayal of domesticity and Kenneally’s is documentary, how do the two artists advance similar or distinct narratives about the role of women in society in public and private spaces? How do these two portrayals convey or fail to convey the ways in which society betrays its mothers and working women, at the same time as it expects them to shoulder such monumental burdens? How do the doorways in The Water Urn and in Three Mothers probe questions about visibility and how we assign or deny the value of domestic labor in society more generally?

The open door in The Water Urn provides a visual entryway into the painting, situating the subjects within the context of a larger domestic space, which we imagine to be just outside of frame. Writing in The Philadelphia Inquirer, Jason Han, MD, utilizes doorkijkje as a metaphorical portal of connection to his patient. Han reflects: “After dinner as lights were dimmed and bedtime was nearing, I returned to the patient’s room. He was speaking to a family member on the phone, so I waved hello and stayed in the doorway until he could finish his call. . . . As I observed, I began to notice the details I had missed earlier. His hair was neatly combed, and he wore wire-rimmed glasses that made him look like a college professor. His gaze was perceptive and ana- lytical. He spoke in resonant, pear-shaped tones as he brought up thoughtful concerns to his wife.”

Chardin’s room within a room view invites the viewer to consider a more contemplative perspective; here, Dr. Han intentionally pauses at a doorway to be more attentive to his patient. How might a similarly thoughtful gaze afford greater recognition and dignity to all individuals in the clinical encounter, whether the patient, caregiver, or those performing essential yet invisibilized labor such as environmental service workers? Like Chardin, how can we honor the communal effort of caregiving in a hospital setting, such that the contributions of each member of the team are valued and the continuity between our otherwise distinct spaces along the spectrum of care is made more visible? If Chardin were to paint the modern hospital, what unseen labor might his doorways reveal and whose lives might he illuminate?

sources

AAMC. “The State of Women in Academic Medicine.” 2013.

“Barnes Takeout: Art Talk on Jean-Siméon Chardin’s Woman Drawing Water from a Water Urn.” YouTube, 27 Apr. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKm50xkUq38&ab_channel=BarnesFoundation.

Bennett, Jessica. “Three American Mothers, On the Brink.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 4 Feb. 2021, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/04/parenting/covid-pandemic-mothers-primal-scream.html.

“Chardin Artworks & Famous Paintings.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/chardin-jean-baptiste-simeon/artworks/.

Han, Jason. “What one resident has learned from listening to patients’ stories.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 14, 2020, https://www.inquirer.com/health/expert-opinions/patient-reflection-doctor-listen-20201014.html.

“Jean-Siméon Chardin .” The J. Paul Getty Museum, www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/533/jean-simeon-chardin-french-1699-1779/.

“Jean-Siméon Chardin.” Artsy, www.artsy.net/artist/jean-simeon-chardin.

“No Tickets for Women in the COVID-19 Race? A Study on Manuscript Submissions and Reviews in 2347 Elsevier Journals during the Pandemic > Gender & Covid.” Gender and COVID-19, 20 Oct. 2020, www.genderandcovid-19.org/resources/no-tickets-for-women-in-the-covid-19-race/.

“Seventeenth Century Dutch Art – Recording the Visual World.” Three Monkeys Online Magazine, 29 Jan. 2016, www.threemonkeysonline.com/seventeenth-century-dutch-art-recording-the-visual-world/4/.

Wilkin, Karen. “Little Women.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 14 Sept. 2012, www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443866404577567002361534704.