Rx 33 / The Sleep of Reason

Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders.

— francisco Goya

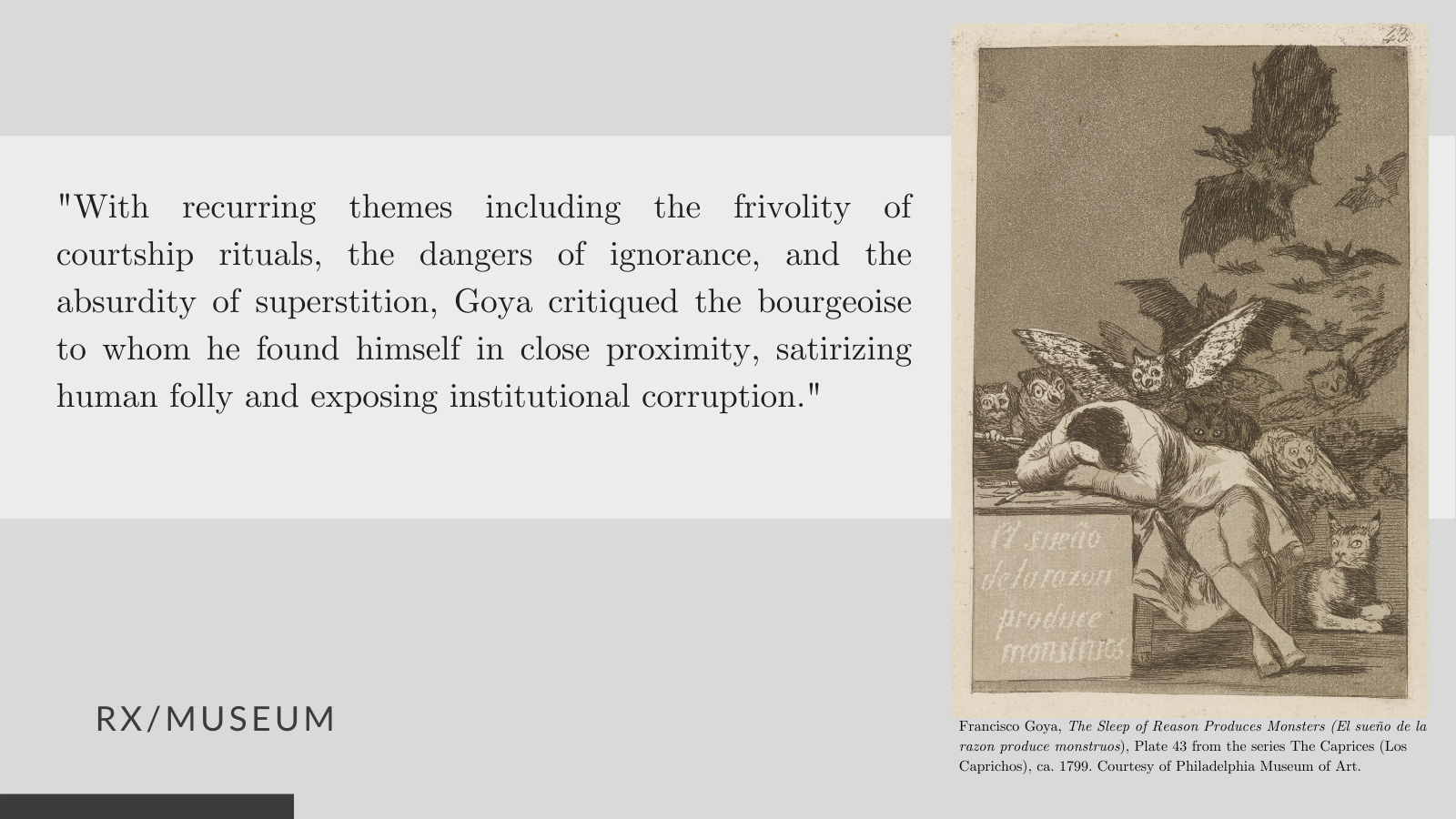

Often regarded as a self-portrait and personal manifesto, this print conveys the struggle between reason and imagination that shaped much of Francisco Goya’s artistic vision. This image appeared in the Spanish artist’s seminal Los Caprichos series of eighty aquatints accompanied by the aphorism,“El sueño de la razón produce monstruos,” or “The sleep of reason produces monsters.” At the turn of the eighteenth century in Spain, Goya’s contemporaries would have recognized the watchful lynx and swarming bats and owls as symbols of ignorance and evil surrounding the reposed subject. Amid the allegorical and nightmarish imagery, the figure’s head hangs despondently over his paper, paint brush, and pen.

As court painter to four successive rulers of Spain, Goya witnessed decades of political turmoil and social upheaval. Unlike his royal commissioned paintings, Los Caprichos chronicles moralizing scenes of daily Spanish life interspersed with supernatural visions, interweaving documentary realism and expressive invention. Capricho, which translates to “whim” or “invention,” suggests the prints were inspired in part from Goya’s imagination. Many of his images of prostitution, witchcraft, and political corruption reveal the impact of the Enlightenment, which espoused that reason should govern thought and behavior. With recurring themes such as the frivolity of courtship rituals, the dangers of ignorance, and the absurdity of superstition, Goya critiqued the bourgeoisie by satirizing human folly and exposing institutional corruption.

Regarded today as a powerful and deeply humane social critic, Goya recorded a turbulent era in Spanish history from a complex vantage both within and outside spaces of power. An advertisement for Los Caprichos from 1799, for example, read,“the artist has selected from the extrava- gances and follies common to all society . . . those which seemed most suitable for ridicule and stimulating as images.” After two days, the advertisement was removed for fear of censorship. Toward the end of the artist’s life, a series of power struggles befell Spain, resulting in successive reigns of terror and violence against citizens. Goya chronicled his nation’s atrocities in his haunting Disasters of War series, even as he fell into reclusive despair and disenchantment. The first group of completed etchings for this series were ominously entitled, “Sad forebodings of what is going to happen.”

reflections…

Goya’s art reflected his proximity to power and social suffering. He sought to find some degree of reconciliation in his art, which at times bordered on surrealism. Healthcare practitioners also struggle with extreme dichotomies in their work: privilege and suffering, empirical rigidity and inherent uncertainty. If Goya’s artistic practice allowed him to process and critique social ills, what medium, figuratively or literally, could clinicians turn to to reconcile opposing tensions and turmoil?

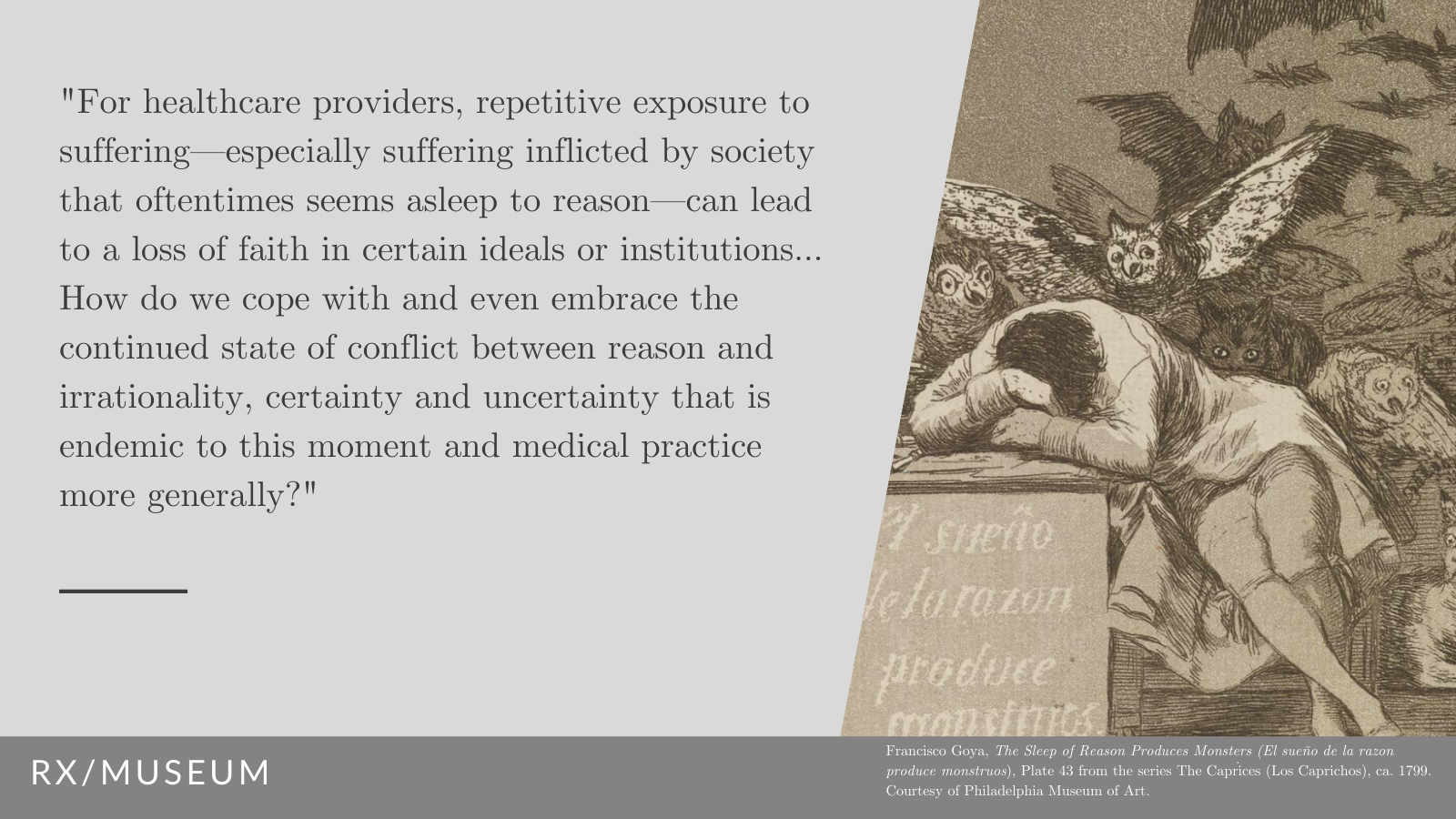

As philosopher Alexander Nehamas writes of Los Caprichos, the series “may praise reason, but they do so only as works of the imagination. It is only on the basis of the imagination that we realize that reason is ‘asleep.’ . . . It is only when both [imagination and reason] work together that each is fully awake.” While Los Caprichos embodies Enlightenment ideals on the supremacy of reason, Nehamas’s interpretation reminds us that Goya intentionally paired rationality with creativity. Likewise, the viewer must rely on reason to interpret the scene, but defer to imagination to grasp its full meaning. Indeed, throughout Goya’s career, his relationship with Enlightenment ideals of truth and reason evolved as relentless encounters with reality led to disillusionment and, eventually, hopelessness and chaos. As embodied in Los Caprichos and The Disasters of War, times of crisis reveal the baser impulses of human nature: cruelty toward one another, fear fueling superstition and mistrust.

For clinicians, repeated exposure to suffering— particularly suffering inflicted by a society that seems asleep to reason—can lead to a loss of faith in certain ideals or institutions. Feeling like the sole or one of the few bearers of reason can produce feelings of anguish and detachment, common sentiments experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic as scientific institutions are frankly ignored or undermined. How do we cope with and even embrace the continued state of conflict between reason and irrationality, certainty and uncertainty, that is endemic to this moment and medical practice more generally? And if, as Nehamas posits, reasoned thought is made more “awake” by compassion and human vulnerability, how can we more effectively appeal to both?

sources

Abbasi, Jennifer. “COVID-19 Conspiracies and Beyond: How Physicians Can Deal with Patients’ Misinformation.” JAMA, vol. 325, no. 3, Jan. 2021, p. 208, doi:10.1001/jama.2020.22018.

Aidan Dunne. “Francisco Goya and ‘the Greatest Anti-War Manifesto in All Art.’” The Irish Times, The Irish Times, 5 Oct. 2017, www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/francisco-goya-and-the-greatest-anti-war-manifesto-in-all-art-1.3245456#:~:text=He%20lived%20with%20the%20reality,he%20lost%20his%20hearing%20permanently.

Eyewitness, Art. “Art Eyewitness.” Art Eyewitness Blogspot, 30 May 2017, www.arteyewitness.blogspot.com/2017/05/.

“Francisco Goya, Los Caprichos.” Auckland Art Gallery, 2021, www.aucklandartgallery.com/page/francisco-goya-los-caprichos?q=%2Fpage%2Ffrancisco-goya-los-caprichos.

Nehamas, Alexander. “‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.’” Representations, vol. 74, no. 1, University of California Press, 2001, pp. 37–54, doi:10.1525/rep.2001.74.1.37.JSTOR.

“Philadelphia Museum of Art - Exhibitions - Witness: Reality and Imagination in the Prints of Francisco Goya.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, 22 Apr. 2017, www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/2017/861.html.

Wikipedia Contributors. “The Madhouse.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 2 Jan. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Madhouse.