Rx 37 / Fairytale

他们从来没有对中国人有如此大的兴趣,谈及他们的时候会眼睛放光,带有奇异的笑容。但这些都很快会过去,最后会成为一种传说,曾经有一个疯子带着1001个疯子来到了这儿。尽管媒体一片叫好声,《童话》的意义并没有被真正理解,我必须每一次把我的话说清楚。在将来更长的时间里,人们会了解这些含义。

Before this, [the Western media and Westerners] never showed great interest in Chinese people, now their eyes beam and they smile strangely when they talk about them. But all this will pass soon, and will eventually become a legend about a crazy man bringing 1001 crazy people to this place. Even though it has been given widespread acclaim from the press, the true meaning of "Fairytale" has not been understood and I have to clarify things every time. People will understand in time.

— Ai Weiwei

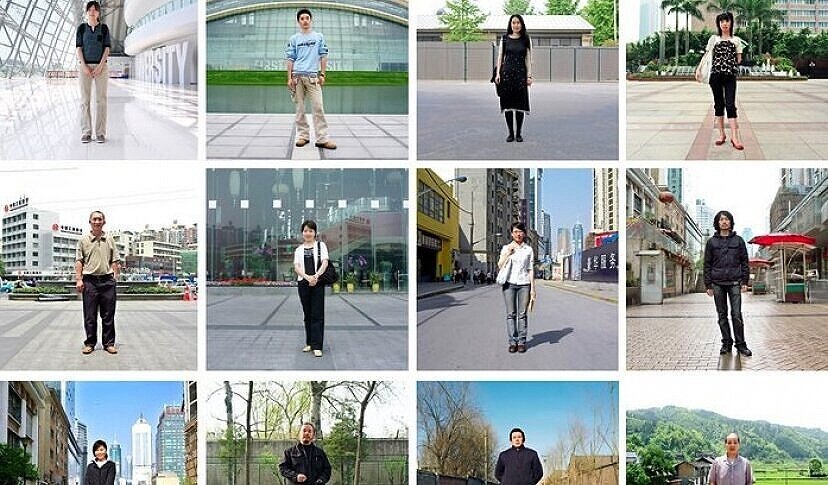

In 2007, Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei initiated Fairytale, a massive conceptual and logistic undertaking that brought 1,001 people from Mainland China to Kassel, Germany. The objective was to view and participate in Documenta 12, a global art convening that occurs every five years in Kassel.The 1,001 chosen individuals were selected through a series of interviews, after which they traveled to Germany in groups of two hundred during the summer of 2007. They lived together in communal housing, briefly experienced life in Kassel, and visited Documenta 12 where Ai Weiwei had installed 1,001 wooden chairs as a physical instantiation of Fairytale. Ai Weiwei explained the piece as “1,001=1,” signifying the fundamental relationship between the collective and the individual.

Like all of Ai Weiwei’s works, Fairytale instigates meaning on multiple levels. Kassel is the heart and birthplace of the fairytales authored by the Brothers Grimm. Ai Weiwei intentionally selected those who could not travel otherwise; a laid-off worker, farmer, or villager from the countryside found themselves on an airplane, participating in cultural exchanges that, under normal circumstances, would have been impossible. As a collective, the 1,001 briefly transformed the body politic of Kassel. As individuals, each brought back distinct experiences to China. This notion carries particular significance for those living in a country where the collective takes precedence over the individual and one’s own hopes and desires are subordinate to the state.

Photographs from Ai Weiwei, “Fairytale,” 2007. Courtesy of Slought Foundation.

Four years after Documenta 12, Ai Weiwei, Hong Kong-based curator Melissa Lee, and Aaron Levy of the Philadelphia-based Slought Foundation began collaborating on Fairytale Project, a research project revisiting Fairytale. The effort brought together a volunteer community to translate, archive, and curate documents collected by the artist over the course of the initial project. In particular, they translated interviews that Ai Weiwei conducted in which participants responded to a series of simple questions (e.g., “What is a dream?,”“What have you gained

from traveling?,”“What would you like to tell the West?”). The answers, preserved and translated on a website (fairytaleproject.net), profoundly assert and interrogate the universality of culture, ethnicity, and society. Fairytale Project, like the original Fairytale, embodies another form of cultural inscription and exchange, wherein participants reflect on identity, memory, love, dreams and the possibility of a cross-cultural dialogue.

Reflections…

We might begin to appreciate Fairytale in the way Ai Weiwei intended if we see it as an unfolding, future-oriented story—a real life fairytale— extending into the present day. The memories and experiences of traveling to and moving through new and unfamiliar spaces have remained with and transformed each individual long after their time in Kassel ended. This movement through unfamiliar space invokes Michel Foucalt’s concept of “heterotopia,” or a place outside of normal life. Heterotopias are generally “privileged or sacred or forbidden . . . reserved for individuals who are, in relation to society and to the human environment in which they live, in a state of crisis: adolescents. . . pregnant women, the elderly.” A heterotopic space—the school, the museum, the hospital— holds a mirror to society at large, contesting and transforming the world around it. Thom Collins, Executive Director and President of the Barnes Foundation, contends,“all who enter heterotopias might be said to participate in a progressive reordering of contemporary social structures and a modeling of new social relations.” Fairytale is its own heterotopia insofar as it establishes a radical, if momentary, alternative to normal life for the travelers. Individuals found themselves existing outside of their daily routine, while Kassel became a slightly different version of itself with a new population and new discursive potential. In this way, Fairytale facilitates not only an out-of-country displacement but an out-of- oneself experience, reminding us that dreams and hopes are essential to a meaningful human experience.

Ai Weiwei suggests that by seeking out possibilities beyond the ordinary, the very pursuit of meaning and fulfillment can be transformative. This concept is in contrast to the stark realities of the COVID-19 pandemic, as clinicians, front- line workers, and so many others have existed, or subsisted, in survival mode. As the pandemic continues, how do we create intentional space and opportunities, a liberatory heterotopia of our own as Ai Weiwei has done, through the arts, dialogue, or other forms of interaction and exchange, to cultivate our intrinsic need for meaning?

In medicine, conversely,“heterotopia” means “out of place” and refers to ectopic tissue “at a non-physiologic site, but usually co-existing with original tissue in its correct anatomical location.” The term implies a retention of origins expressed through movement and migration. How does Fairytale remind us of the challenges of identifying with and reconciling pluralities, of being “other”? Ai Weiwei stated his project would be viewed as novel, and nearly magical in its transformative aspect for the participants. His questions aim directly at the notion of dreams and individual growth. However, experiencing foreignness is bidirectional. Just as the travelers move through a new environment, their presence will simultaneously be perceived as heterotopic by the existing community. Their identities will be defined both at the individual and collective levels. In the context of anti-Asian hate and violence in the United States that is fueled by discriminatory rhetoric related to COVID-19, how do we protect vulnerable individuals from being stigmatized and profiled? How is this moment particularly traumatizing for those with multiple marginalized identities within a heterotopic space, such as Asian Americans who are also frontline workers?

Sources

Ai Weiwei. “童话项目 / Fairytale Project / Fairytale-Projekt.” Fairytale, fairytaleproject.net/.

Burnbaum D. Ai Weiwei: Fairytale: A Reader (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2012).

Collins T, Foucault, M. Somewhere Better Than This Place: Alternative Social Experience in the Spaces of Contemporary Art (Cincinnati: Contemporary Arts Center, 2003).

Lee M, Levy A. Fairytale Project, Slought Foundation, 2011-2014, https://slought.org/resources/fairytale_workshops.

Jiang, Y. “The Social Subversion and Improvement of the Relationship– Ai Weiwei's ‘Fairytale.’” Medium, Medium, 16 Nov. 2018, medium.com/@yijunjiang_61375/the-social-subversion-and-improvement-of-the-relationship-ai-weiweis-fairytale-f187803d11dd.